|

From the Archives Drawing lessons: G. R. Santosh's Comic BookAnkan Kazi June 01, 2023 What is the place of illustrations in modern art? As western artists have increasingly formalized the adaptation of comic book and illustrative vocabularies in modern art, at least since the days of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Indian artists have been responding to or adapting commercial print cultures in their work for a considerable period of time as well. Drawing from popular cultural references and prints that were available widely and cheaply across the country, artists have reacted reverentially or nostalgically, critically and ironically to these works and their everyday practices of production. Some have also turned to comic book illustrations as a part of official commissioned work. The Indian artist G. R. Santosh was one such artist who illustrated a comic book titled ‘Lakshman Kills a Tiger’. Read more to find out what this comic was about. |

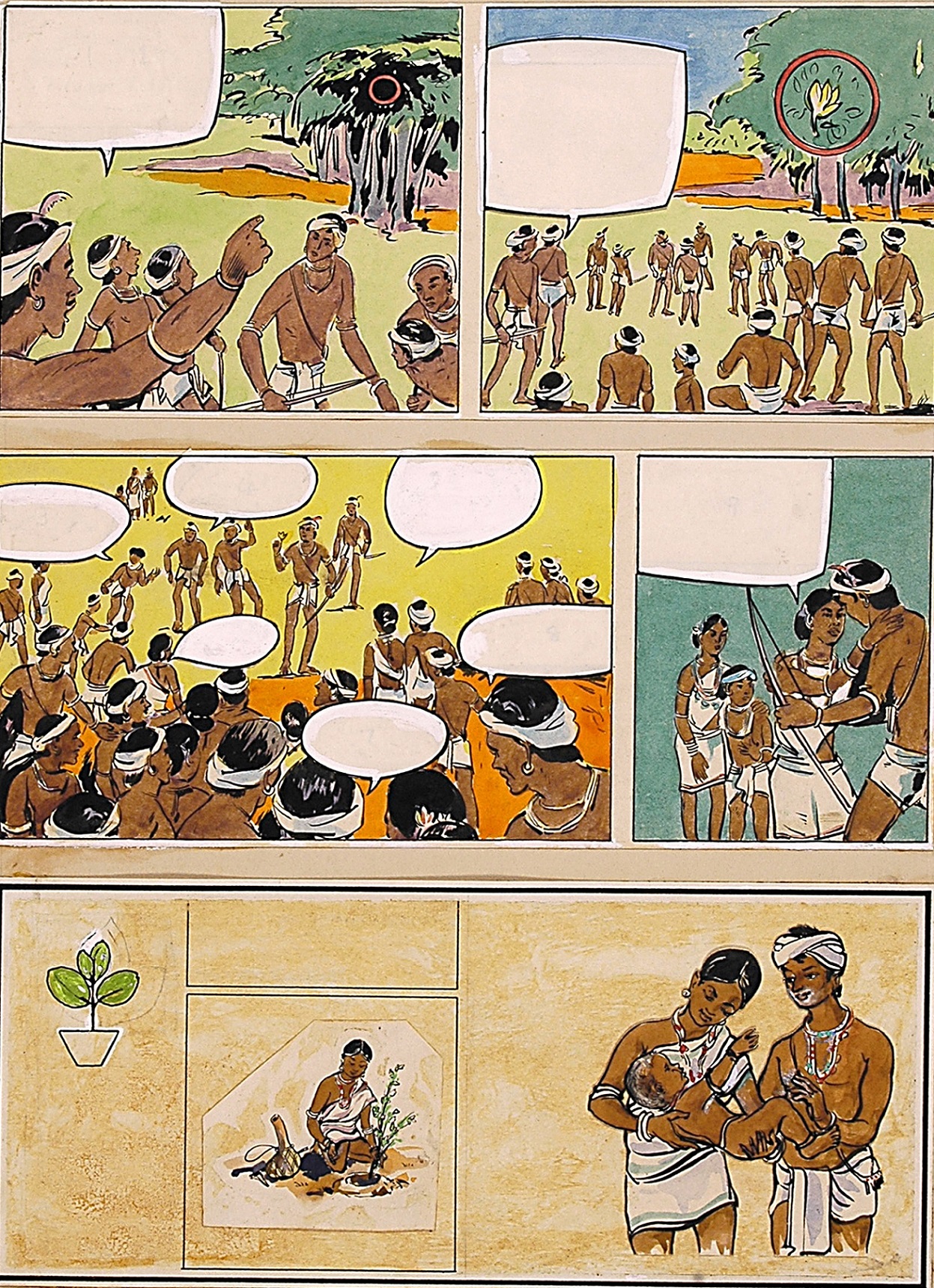

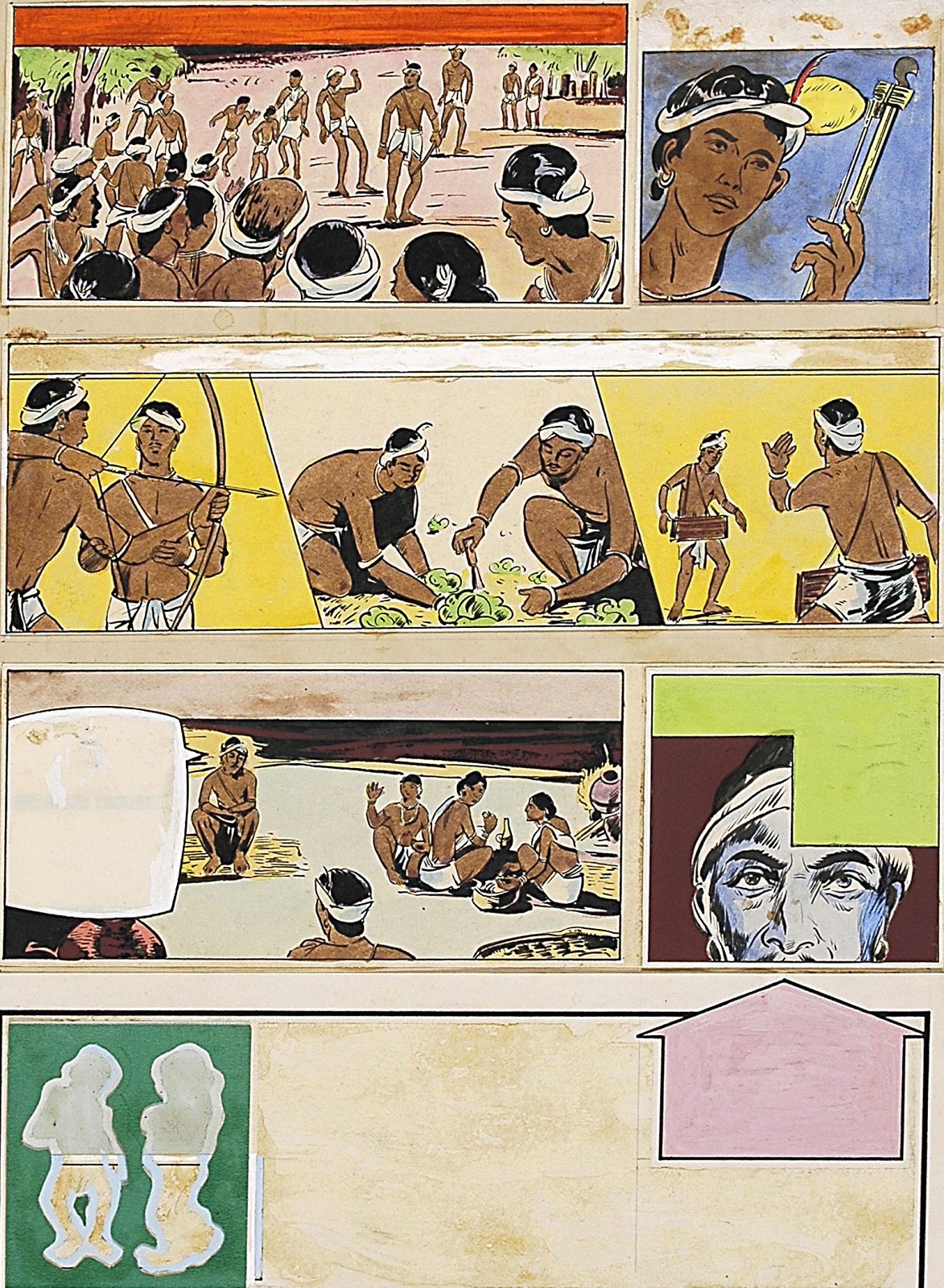

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) (detail), 16.2 X 13.0 in.

Gouache, ink and collage on mount board

Collection: DAG

|

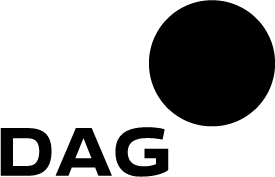

G. R. Santosh (1929—1997), born Gulam Rasool Dar, was one of the great experimental modernists of the post-independent era. He was born in Kashmir, where he worked on several types of art-making such as silk weaving, papier-mache handicrafts and painting billboards, houses and truck art—the lifelines of commercial painting practices across the country, until a chance meeting with S. H. Raza propelled him onto his career as an artist. |

|

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in. Gouache, ink and collage on mount board Collection: DAG |

G. R. Santosh, Untitled, 30.0 x 24.0 in.,1993

Acrylic on canvas

Collection: DAG

G. R. Santosh, (Untitled Tantric Drawing 5), 10.5 x 8.2 in.

Ink on paper

Collection: DAG

Aside from his writing, Santosh is now known for his formal, aesthetic expressions of Kashmiri Shaivism through his neo-tantric art that became a hallmark of his style after a revelatory visit to the Amarnath cave in southern Kashmir in 1964. However, Santosh maintained various other aspects of his art practice. One reason for this could be the difficult and controversial reception of his new works by art critics and the market, both of which were still developing their vocabularies around defining Indianness as a feature of modernist practices that were otherwise learnt from various formal experiments across the world. |

|

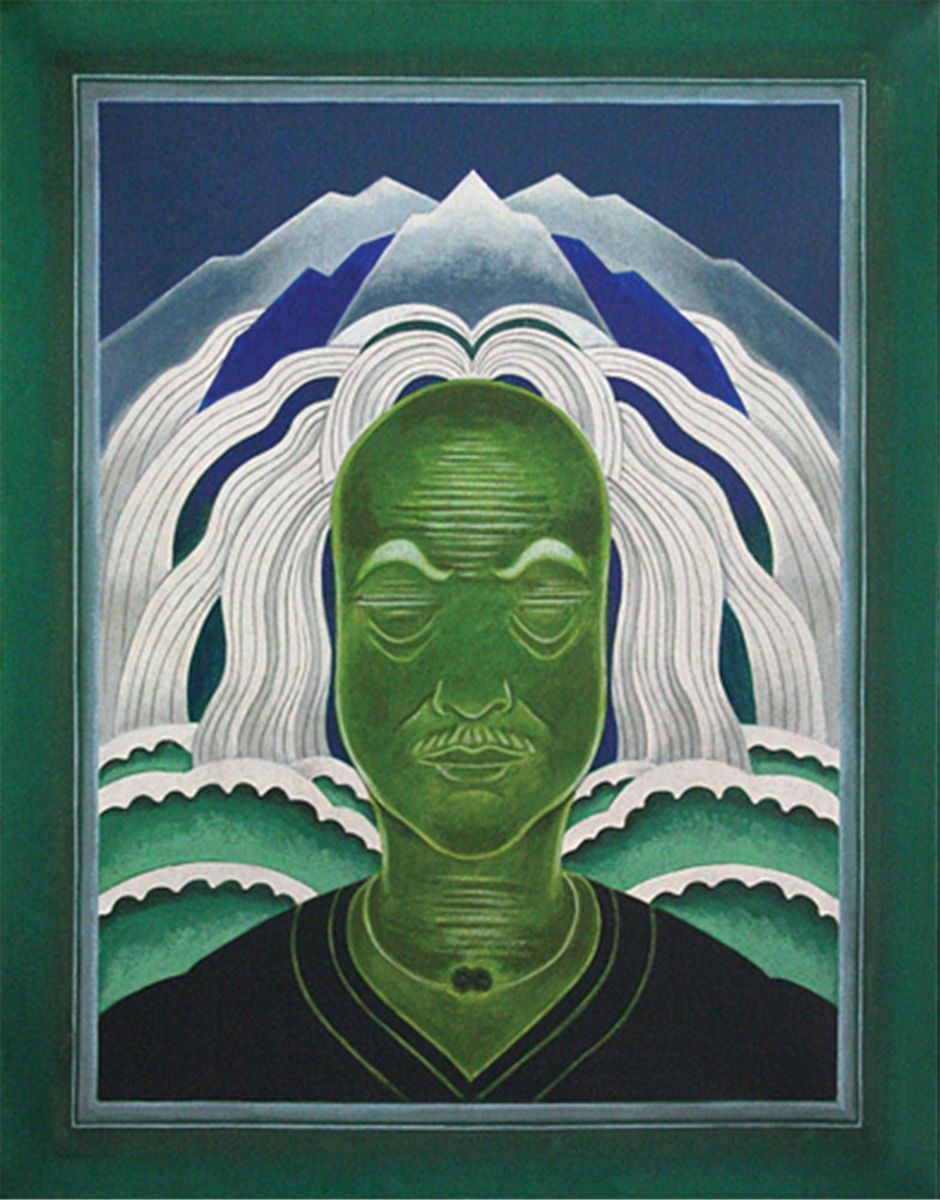

Thus, some of the more forgotten aspects of Santosh’s work includes the various designs he made for government agencies after he had started living in the capital city of New Delhi, such as the logo for Jammu and Kashmir Tourism, featuring a shikara (now replaced), or various banknotes (now discontinued) that featured some of the modern icons of the Indian state: such as tractors (for the 5 Rupee note) or dams (for the 100 Rupee note, which featured the Bhakra Nangal dam). His design for the Indian 20 Rupee note featured the iconic Konark wheel. |

|

Old Twenty Rupee note Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Old 100 Rupee note

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Old 5 Rupee note

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

A. Ramachandran, Stamp of India, 1982, for the Asian Games in New Delhi

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

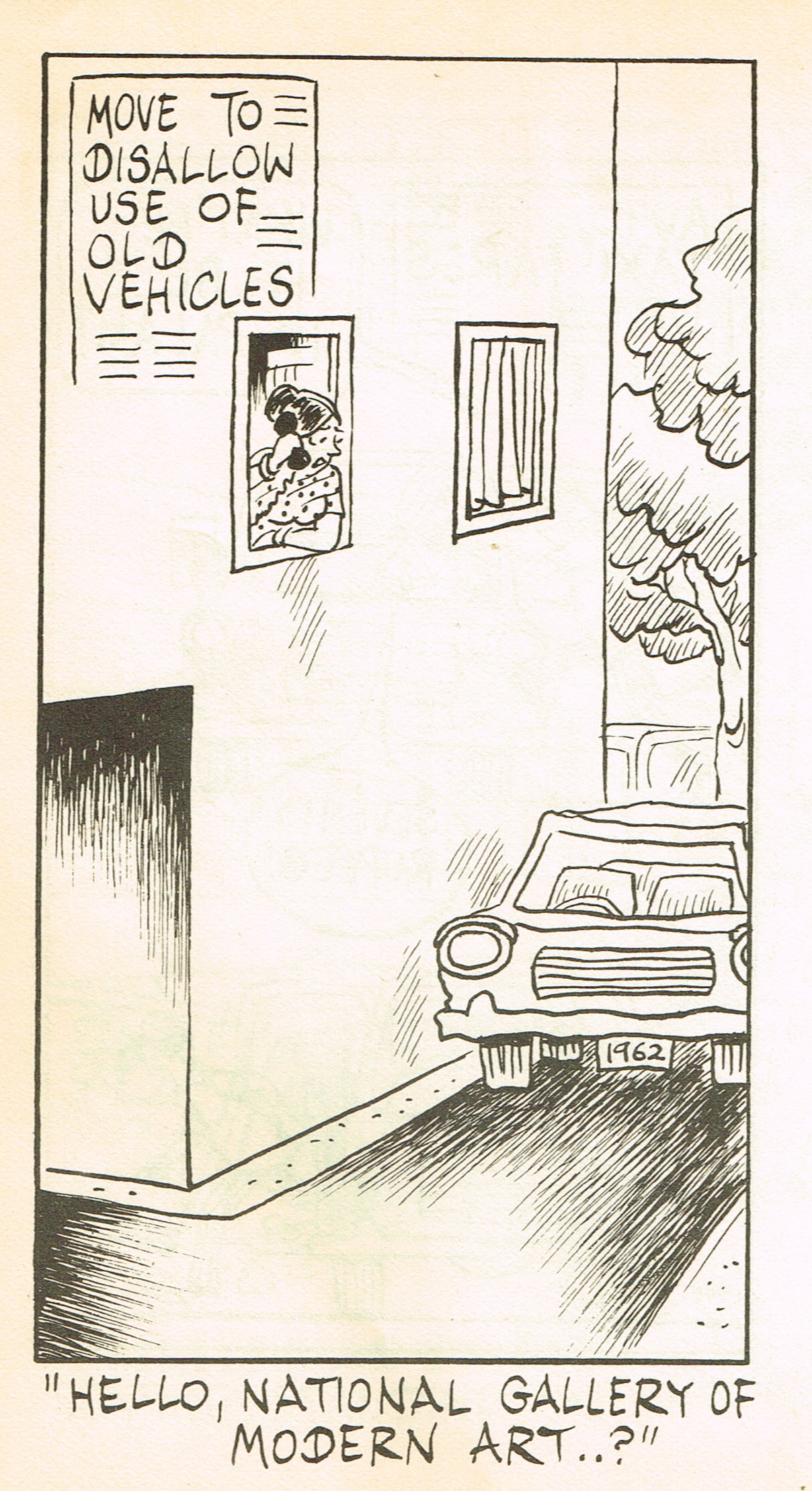

Sudhir Dar, cartoon print

Image courtesy: Ashok Bhatia

He designed special sets of stamps that were issued during the Asian Games in 1982, along with other artists like A. Ramachandran and Chitta Pakrashi. Santosh’s commercial work also included designing book covers for his writer or poet friends, although the word ‘commercial’ needs to be read loosely here as he did some of this work gratis, as favours to friends, according to his son Shabir. Santosh was a well-regarded portrait painter for most of his career, making portraits of luminaries from the political and cultural world of New Delhi, but his figurative and illustrative work was largely confined to alternate, commercial practices even as he maintained an active relationship with fellow-illustrators and cartoonists. For instance, he was a friend of Sudhir Dar, a fellow-Kashmiri and well-known cartoonist. |

|

He also illustrated a comic for ‘Children are Precious’, which was probably a charitable aid organization based out of New Delhi’s Nizamuddin West, and a contractor for CARE. What was this comic book about and who were the commissioners? Let’s find out. |

|

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in. Gouache, ink and collage on mount board Collection: DAG |

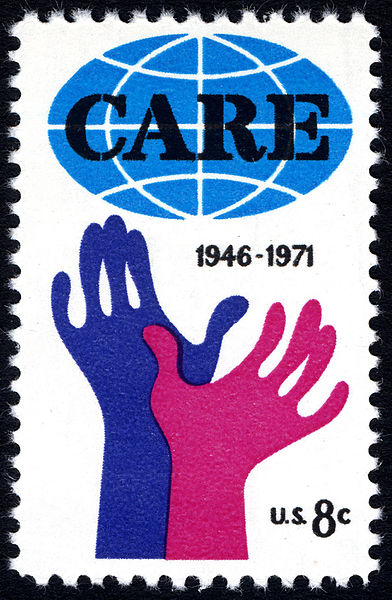

Soren Noring, CARE commemorative U.S. stamp.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

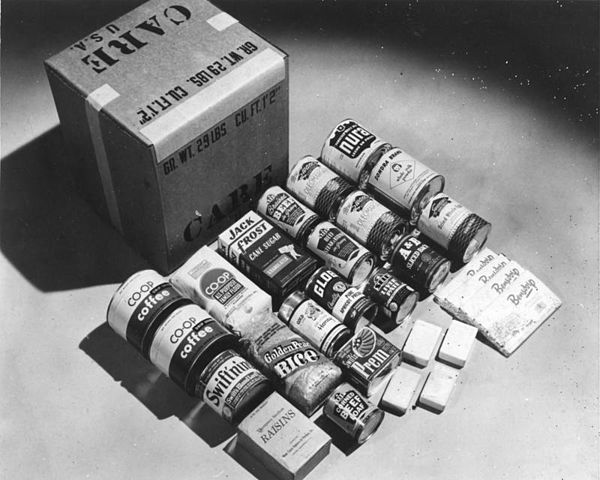

A CARE package sent out in 1948

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

CARE stands now for Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, changed from its former Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe. One of a slew of aid and humanitarian relief organizations formed after the Second World War (in 1945), CARE focuses on problems of global poverty, food security, agriculture and water sanitation among other projects while advocating for policy reform on behalf of poorer populations across the world. |

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in.

Gouache, ink and collage on mount board

Collection: DAG

Advertisement poster for the Instan State Railways, printed at the Bolton Fine Art Litho Works

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

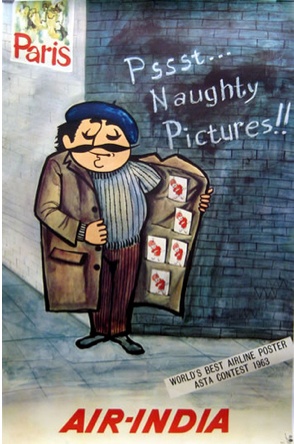

The comic book was printed by N. J. Ardeshir for the Bolton Fine Art Litho Works printing company that was based out of Bombay (now Mumbai) and was operational largely through the middle and late decades of the twentieth century. They are responsible for printing some of the most iconic images in Indian commercial design and advertisement art, including several offset lithographic posters for Air India and tourism posters for Indian destinations such as Banaras (now Varanasi) and Kashmir, among many others. The government of India was thus a major, recurring client. The press also plays an important historical role as Parmanand Sugomal Mehra, who worked at the company, took it upon himself to lead the creation of a pan-Indian association of small printers and presses, called the All India Federation of Master Printers in 1953. |

|

Lakshman Kills a Tiger |

|

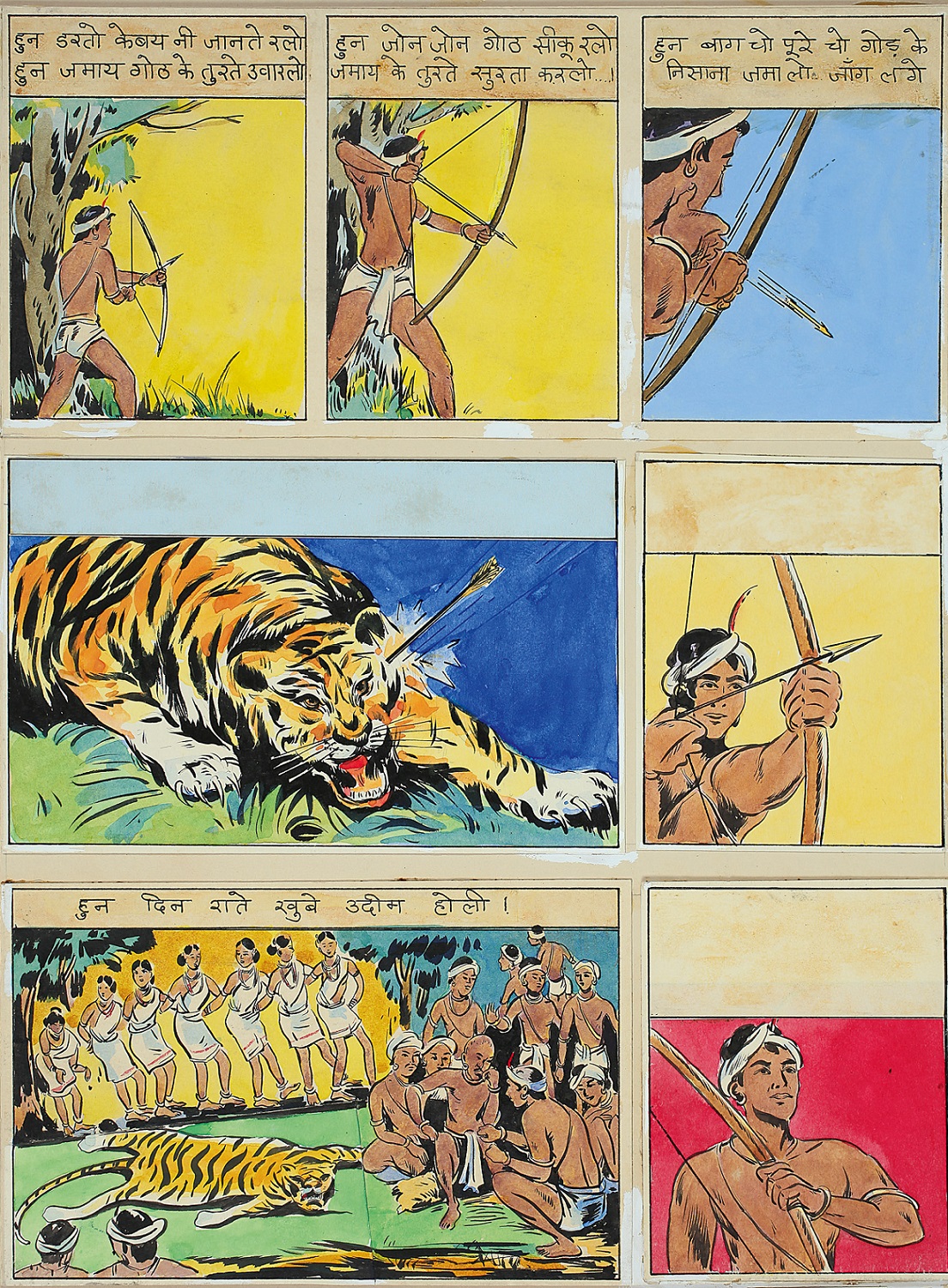

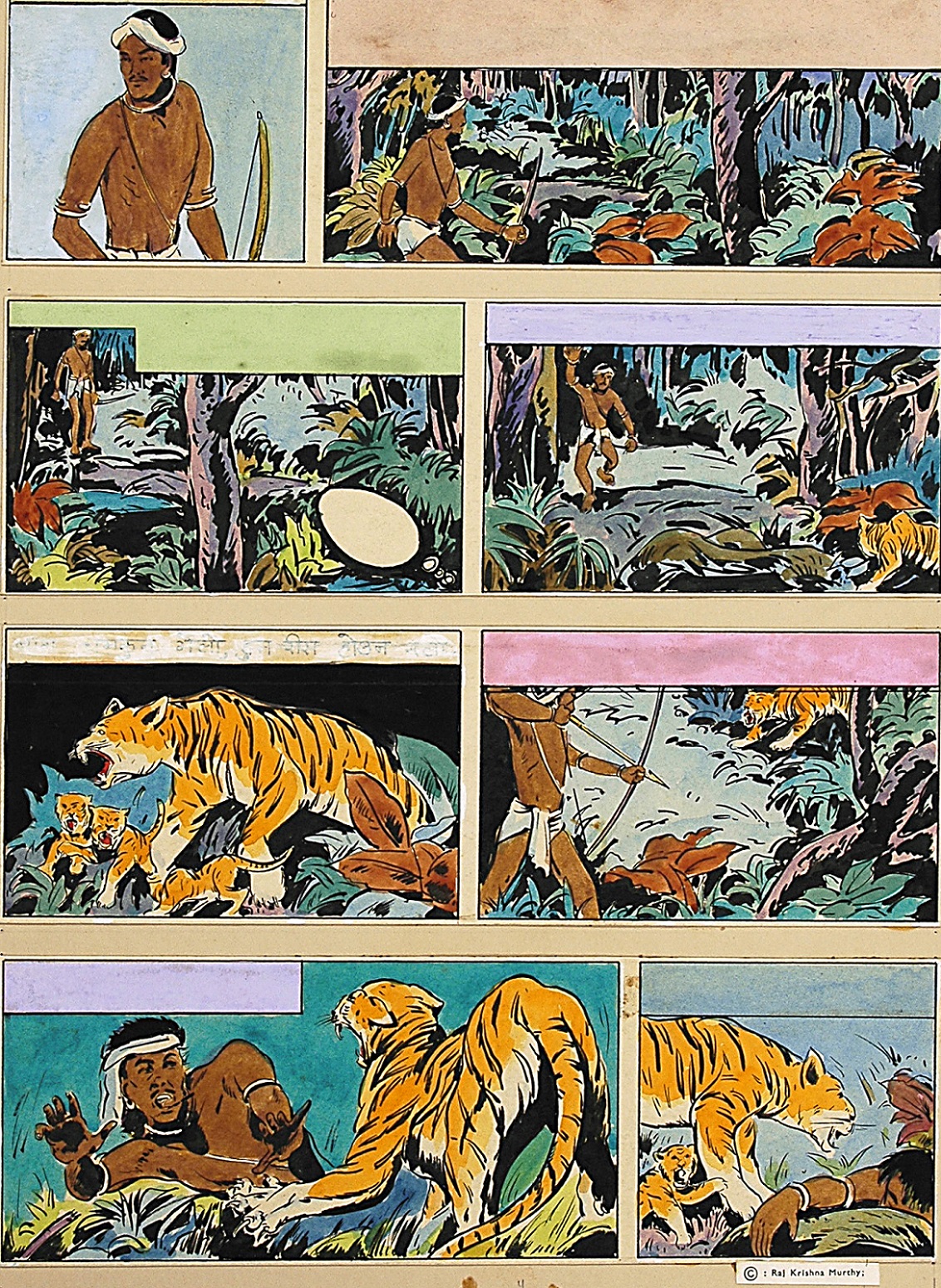

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in. Gouache, ink and collage on mount board Collection: DAG |

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in.

Gouache, ink and collage on mount board

Collection: DAG

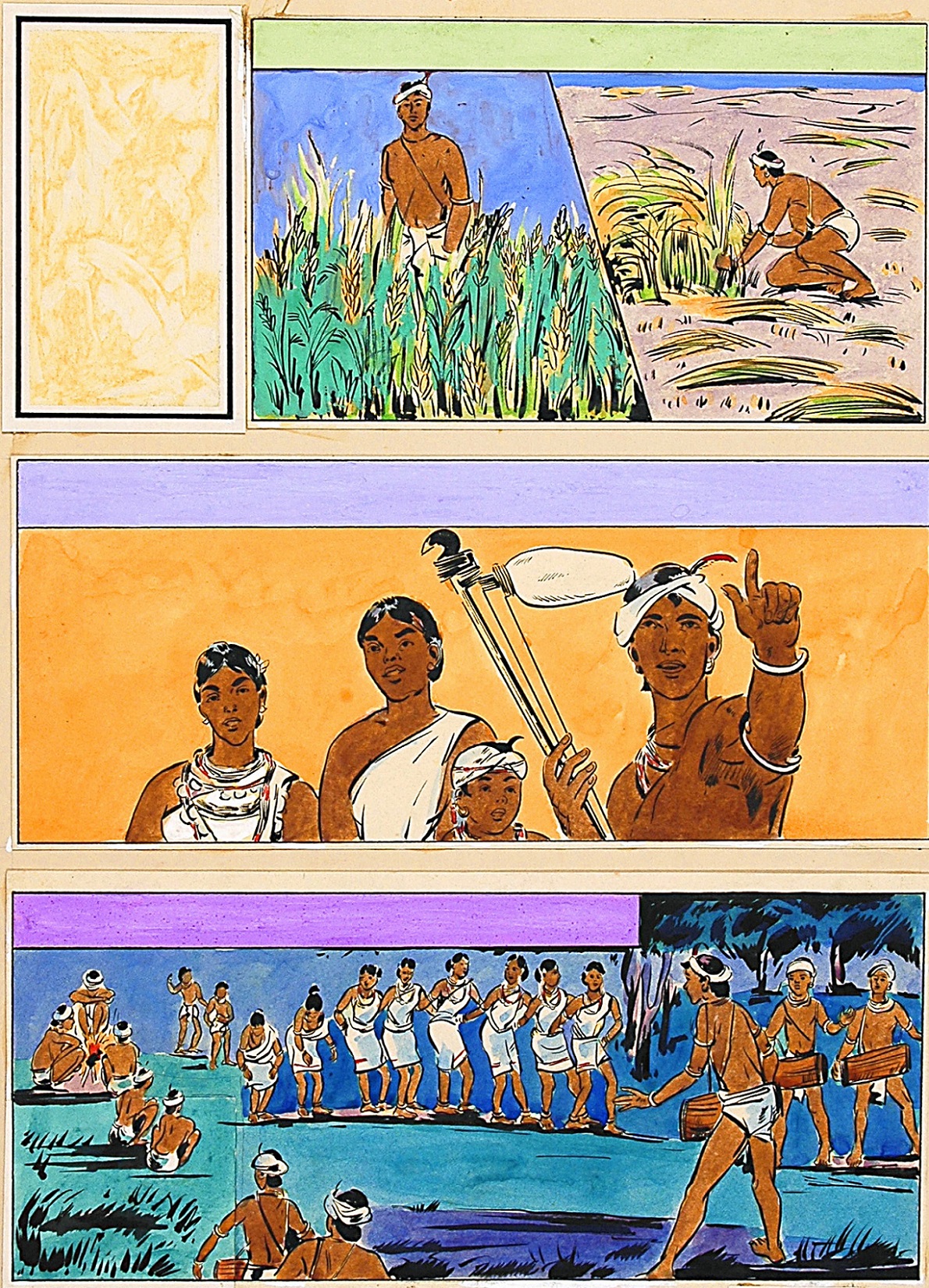

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in.

Gouache, ink and collage on mount board

Collection: DAG

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in.

Gouache, ink and collage on mount board

Collection: DAG

The story begins with a simple set up: ‘India has a wealth of forests. Many beautiful animals live in them. Some people also live in these forests. This is a story of a small family of these people: The story of Lakshman, his father Jethu, mother Baisakhi, brother Mangal, and sister Phalguni.’ Lakshman is presented as the courageous and likeable protagonist of the story. His father, Jethu, from whom he has learnt most things has taught him the most valuable lesson that was denied him in his own childhood, however, saying, ‘A house without a kitchen garden is not a home….Grow proper food for health, strength and intelligence.’ This lesson underscores the purpose of the comic and highlights the difference between Jethu and Lakshman as acceptable patriarchal models for the village community. ‘Jethu’s health had suffered since his childhood’ because his parents had not known about the importance of early childhood nutrition, which could make children ‘weak and listless’ and cause them to ‘suffer during (their) entire life’. |

|

The comic also refers to another radical change that was blowing across rural India at the time, transforming agricultural practices and pushing farmers into global circuits of farm economy and technological change. The introduction of high-yielding varieties of seeds, mechanized tools, new techniques of irrigation—mostly spearheaded by economists and agronomists such as the American Norman E. Borlaug (who won the Nobel Peace Prize later) and India’s M. S. Swaminathan, along with many others—led to what has commonly been described as a ‘Green Revolution’. When Jethu hears from someone, ‘I have heard that new seeds have arrived.. with higher yields’, he immediately wants to go to the market and buy some for his ‘kitchen garden’. It is worth noting that the effects of the Green Revolution were not evenly spread across the country—especially skipping parts of tribal-occupied areas like Bastar. Even though the production of wheat and rice doubled due to the ‘revolution’, the production of other food crops such as indigenous rice varieties and millets declined. This led to the loss of distinct indigenous crops from cultivation, in many cases causing certain varieties to go extinct. |

|

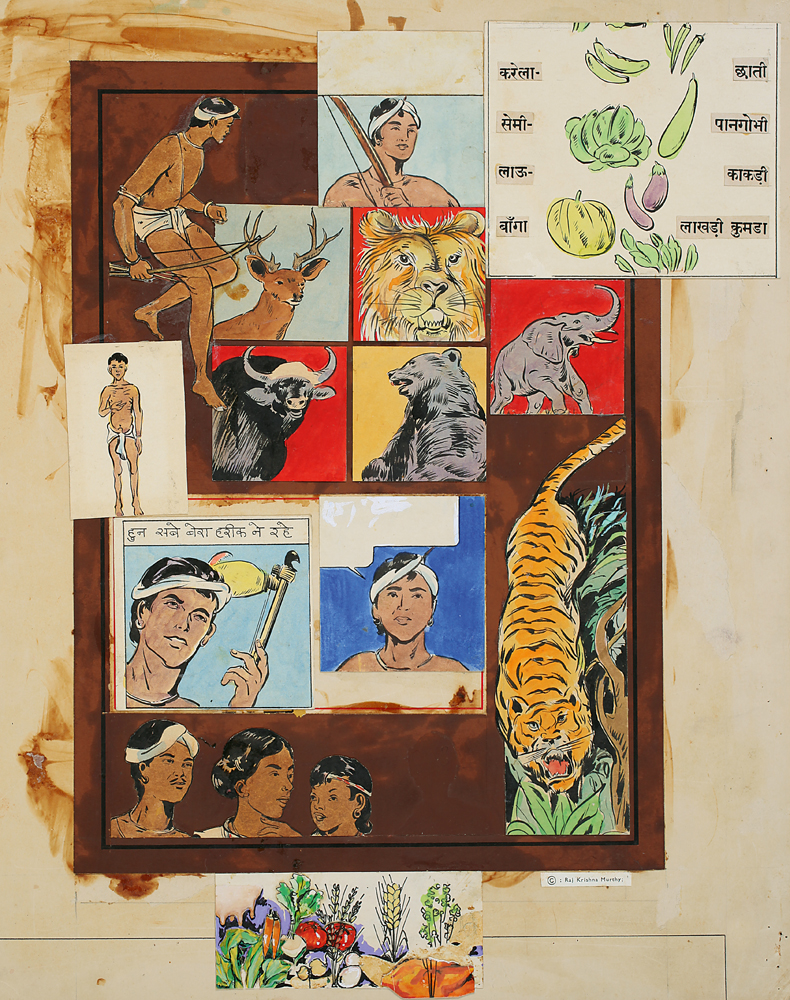

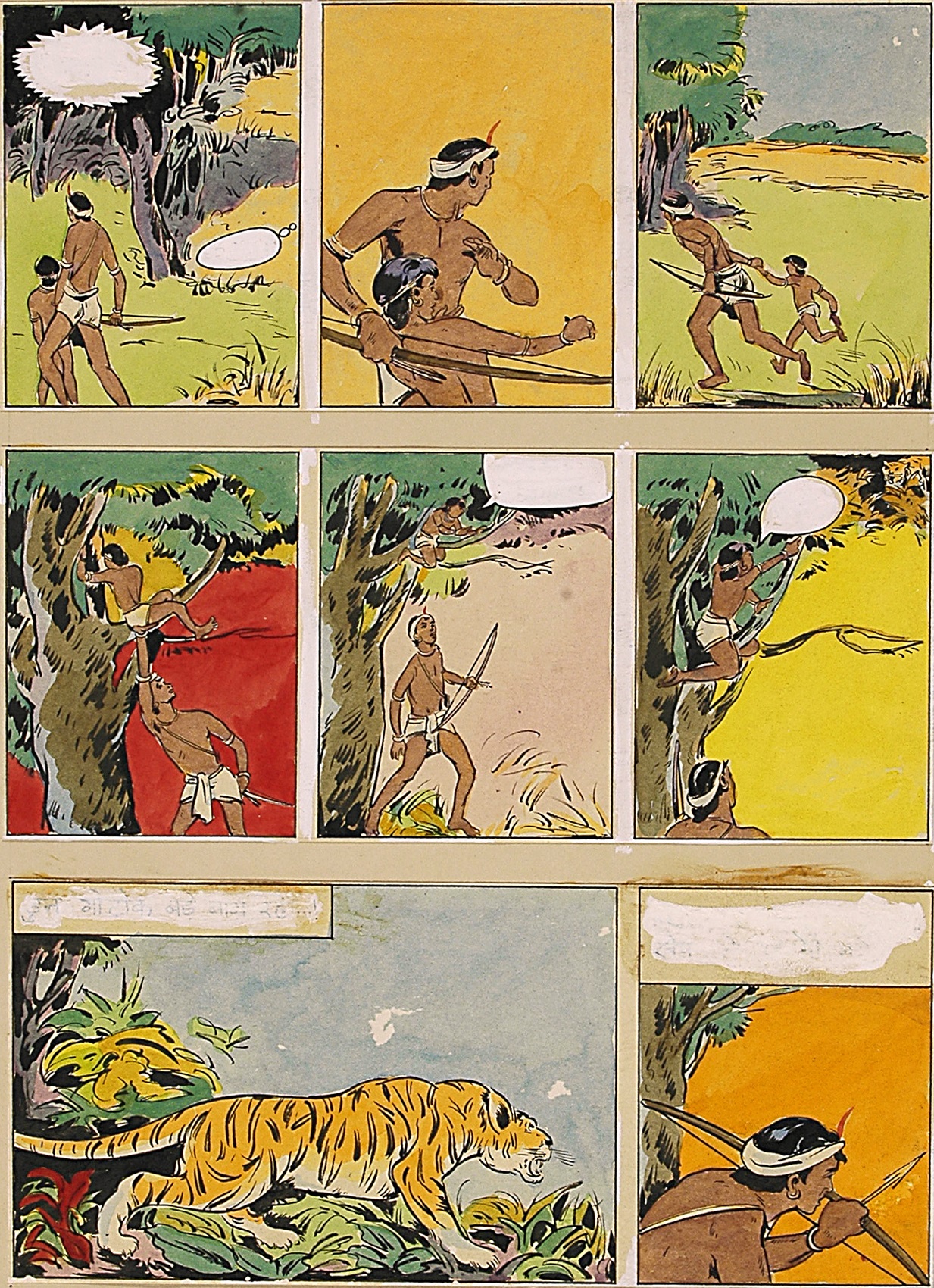

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in. Gouache, ink and collage on mount board Image courtesy: Jesh Krishna Murthy |

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in.

Gouache, ink and collage on mount board

Collection: DAG

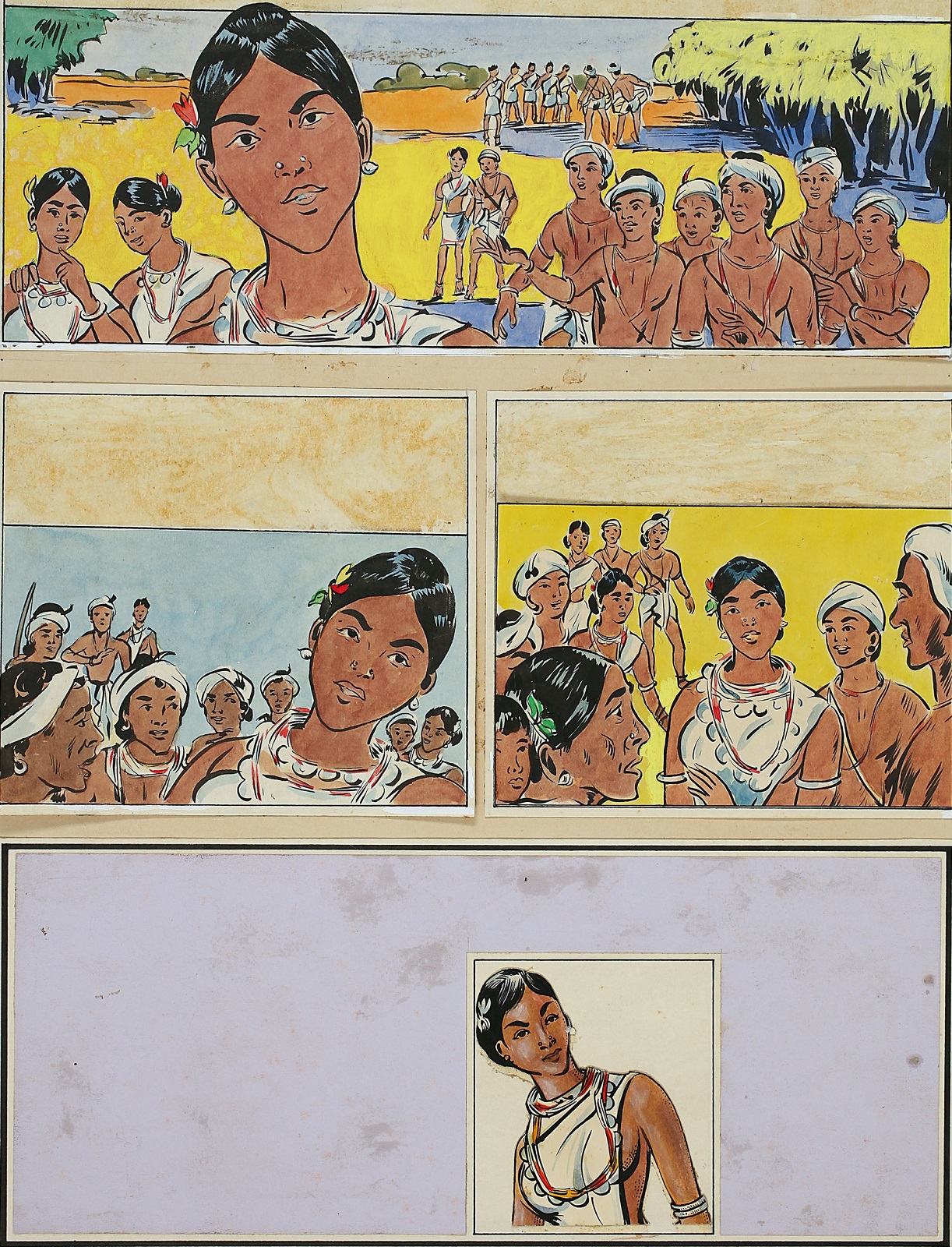

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in.

Gouache, ink and collage on mount board

Collection: DAG

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in.

Gouache, ink and collage on mount board

Collection: DAG

G. R. Santosh, Untitled (Illustration for a Children`s Book on Nutrition) , 16.2 X 13.0 in.

Gouache, ink and collage on mount board

Collection: DAG

Jethu is attacked by a tigress and unable to defend himself due to his early life malnutrition. As a sense of gloom settles upon the family, Baisakhi continues her good work by providing healthy food to her children. Soon, harvest season arrives—bringing with it a mood for celebration and festivities. Phalguni, now a young woman, is admired for her good looks and we are informed by a narratorial text: ‘Like most people they didn’t ask how she maintained such good health… she would have answered that proper diet was not only for good health, but for good looks too’. Soon, the villagers discover that another aggressive tiger is on the prowl. Some of the men think Lakshman may have compromised his masculine valour by ‘sell(ing) vegetables’ on the market, so he is put through a target test, which he aces. Lakshman is further emphasized as the ideal hero who speaks in the voice of the pedagogical and developmental state when we are informed about his education and association with the local school, where he went to help the teacher: ‘…even elders came to listen because Lakshman spoke of such useful things’. |

|

'The Fearless One' In a few years, as their farm and home grow under their care, the tiger reappears threateningly and the new patriarch-in-waiting, Lakshman, has to kill it like a hunter. He does that successfully and earns the nickname ‘The Fearless One’. This event allows the writer of the comic to establish Lakshman’s moral righteousness and natural claim to be a progressive leader, while rounding up his lessons on the all-round value of nutrition from an early age. The comic ends with a chart that recaps these lessons, suggesting: ‘For Good Health, Good Taste, Good Looks, Choose Foods From Each Group Everyday’, followed by a list of food items presented according to their nutritional categories (such as sources for protein, vitamins, carbohydrates, etc.). Santosh is successful in creating a world with simple lines and expressive gestures. The colour palette ranges between strong bands of primary colours, and variable Indian skin tones, to anchor the attention of children and code the messages on nutrition in an efficient manner. His depiction of the flora and fauna is illustrative of their nutritional properties as well as their aesthetic appeal. Comics such as these were widely available at the time, and ultimately functioned somewhat like the instructional films made by the erstwhile Films Division of India, where popular cultural forms were negotiated with the stern but benevolent hand of moral and ethical guidance. |

|

|