FAMINE

The Bengal famine of 1943 is a complex and contentious period in our colonial history. Taught in Indian schools as part of the history curriculum, this event has been studied extensively through various historical and political lenses. This resource pack is curated with the aim to equip educators with primary sources such as artworks and newspapers as well as secondary sources like essays that can engage students as active learners in the classroom.

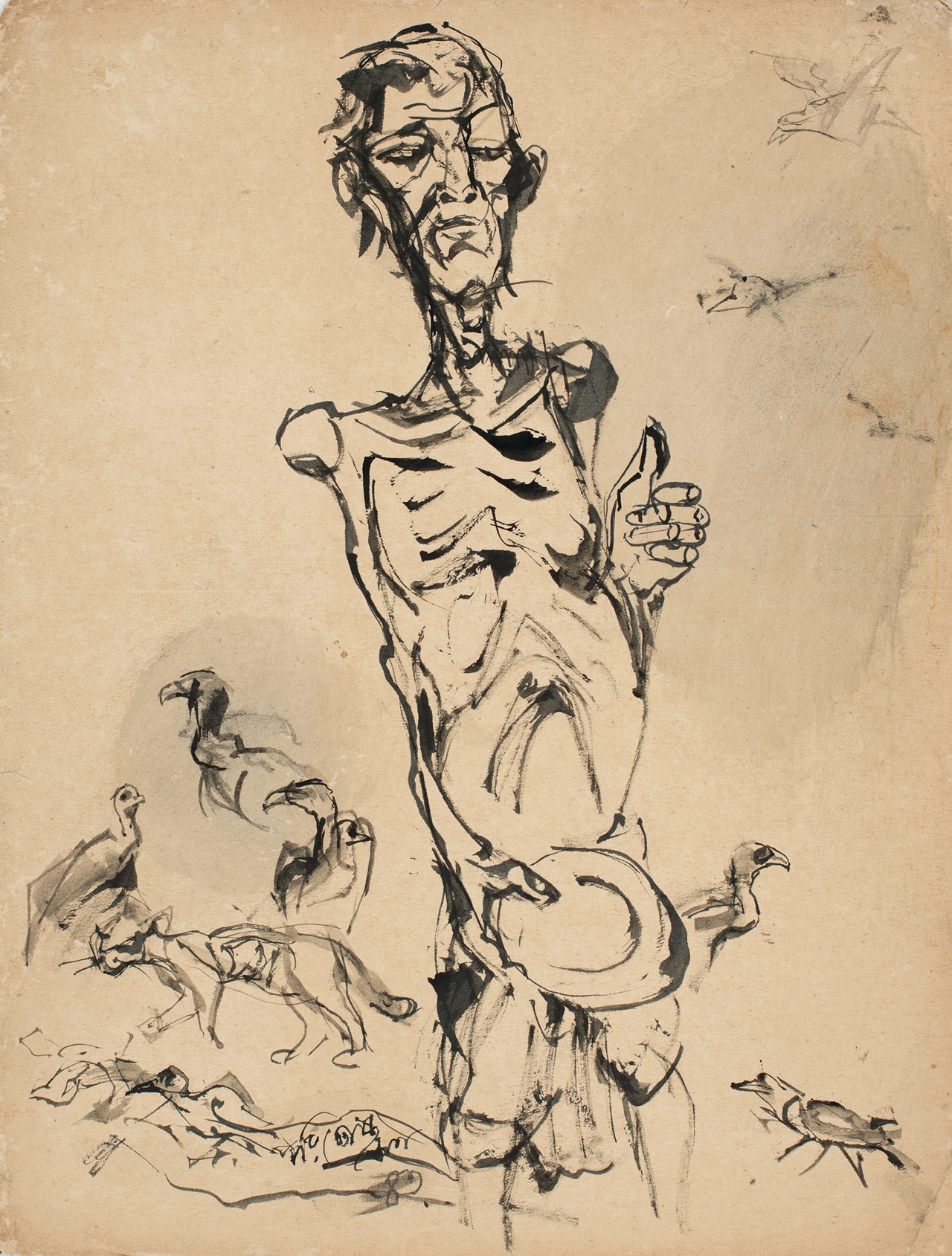

Chittaprosad

Halisahar, Chittagong 1944

Ink on paper

DAG Museum Collection

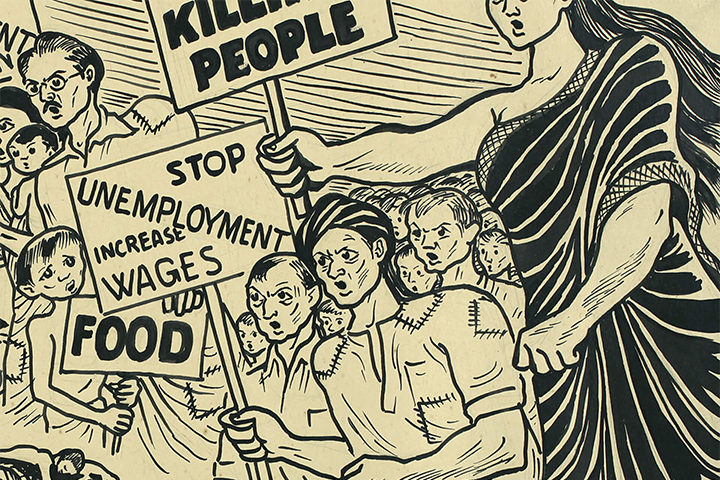

Paritosh Sen

Untitled

Ink on paper

DAG Museum Collection

Chittaprosad

Untitled

Linocut on paper

DAG Museum Collection

Zainul Abedin

Untitled 1942

Woodcut on newsprint paper

DAG Foundation Collection

Chittaprosad

Purna Sashi 1944

Ink on paper

DAG Archives

Gobardhan Ash

One by One 1943

Water colour on paper

DAG Collection

Ramkinkar Baij

Untitled 1943

Water colour and ink on paper

DAG Museum Collection

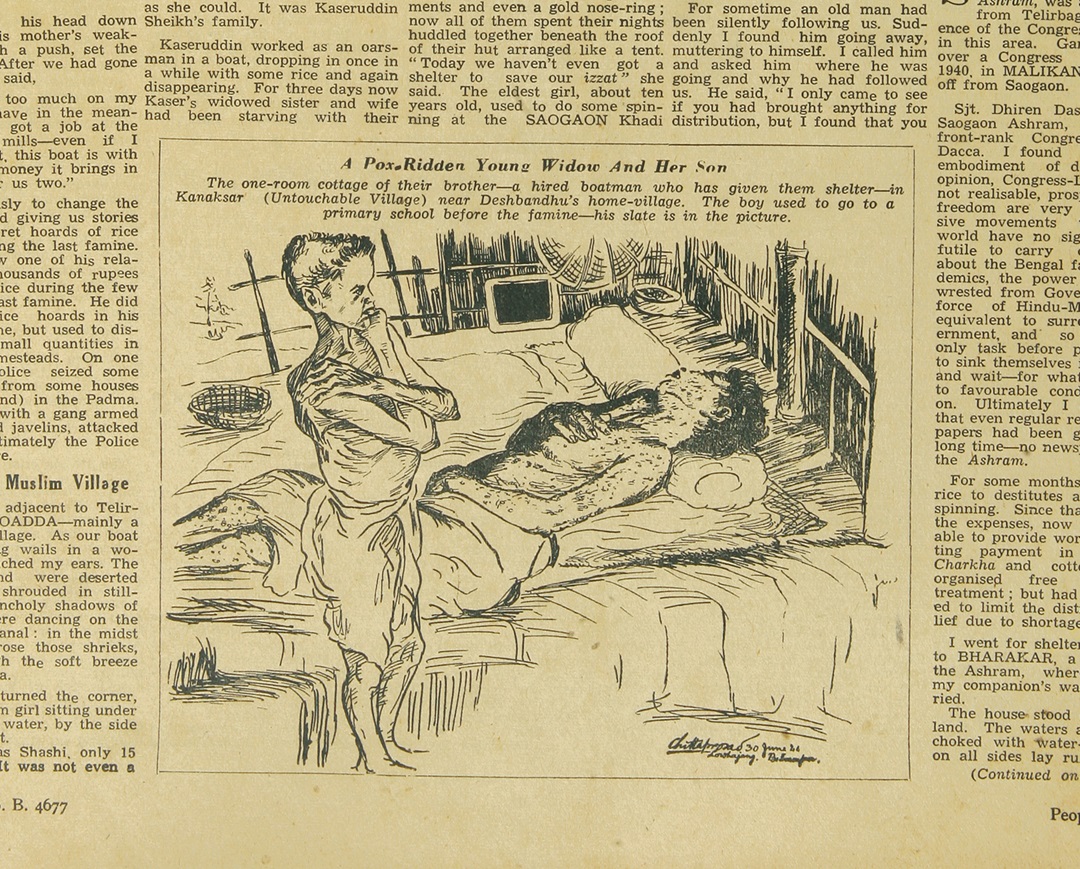

Chittaprosad

A Pox Ridden Young Widow and Her Son from People’s War 1944

Newspaper print

DAG Archives

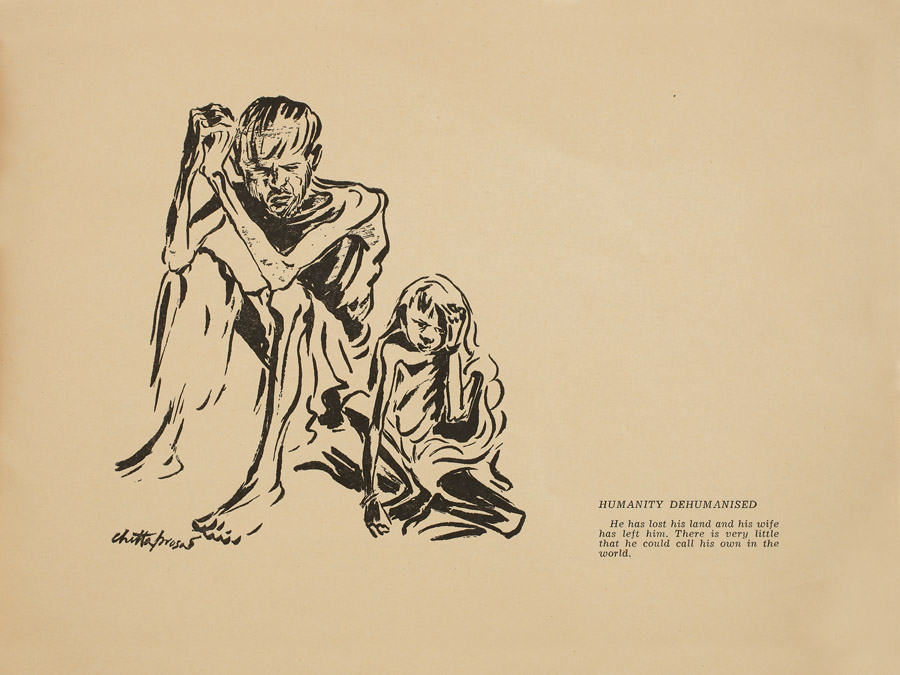

Chittaprosad

Humanity dehumanised from Hungry Bengal 1943

DAG Archives

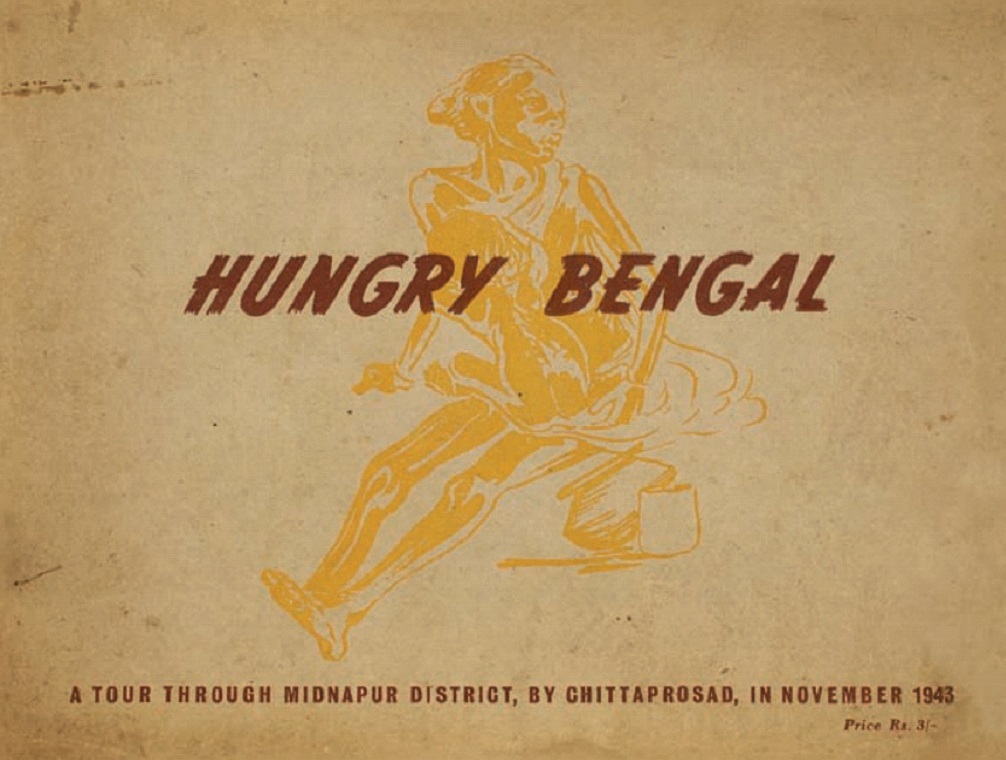

An excerpt from Chittaprosad’s Hungry Bengal

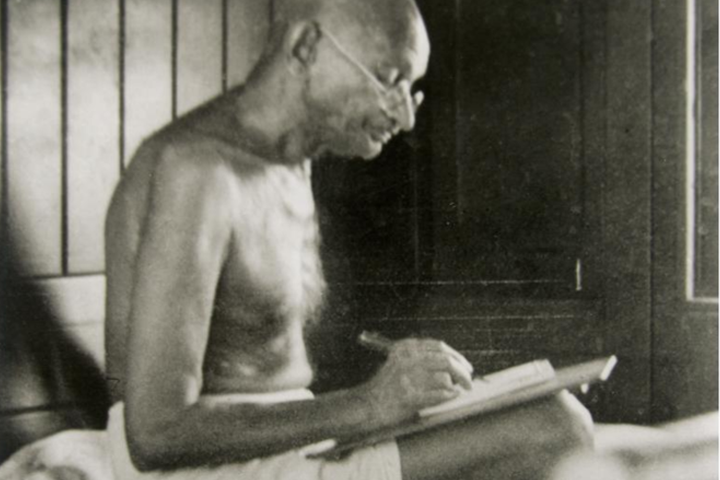

Artist Chittaprosad, an active member of the Communist Party of India (CPI), travelled across Bengal during the famine and documented through sketches and journal entries his eyewitness accounts of the conditions in the streets of Kolkata as well as Contai, Bikrampur, and other regions of the former Midnapore district.

Many of his writings and sketches were published in prominent communist publications of the time. A set of twenty sketches, along with some of his journal entries were published as a volume titled ‘Hungry Bengal’, which was met with suppression by the British authorities, resulting in only one copy of the book surviving. Hungry Bengal was republished by DAG, and here an excerpt from it has been reproduced.

THE MAN-MADE ‘FAMINE’ IN BENGAL

Sanjoy Kumar Mallik

William Vandivert: A starving child stuffing himself with creamy food, 31 Dec 1942, (Image Courtesy: Time Life Pictures, Getty Images)

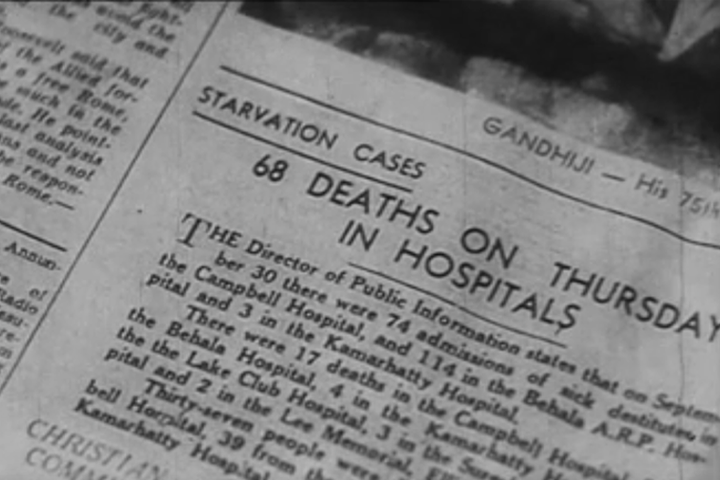

Since the cultural practitioners of the Communist Party responded prominently to the disastrous conditions of the man-made famine in Bengal, it assumes the identity of a catastrophe of distinct significance. As early as September 23, 1943, the ‘man-made’ nature of the disaster had already been recognized, implying that human intervention itself could have averted the suffering, or at least the degree of it.

The roots of the disaster can be traced back to 1939, the association of India with Britain’s war on Germany that raised voices of protest but could not resist the drain of resources from the country being channelled into war-efforts. The war no longer seemed distant when the fall of Rangoon to the Japanese cut off the supply of rice from Burma. The Quit India call of 1942 that stirred up a determined movement in Tamluk and Contai sub-divisions of Midnapore district brought severe repressive measures as backlash. The repeated bombings on Chittagong caused much damage as well as raised a threatened tension in Calcutta. Soldiers of the Allied forces were stationed to combat. Amidst the bleak circumstances that had seriously disruptive effects on the economy of the region (with disastrous policies like the ‘boat denial’ and ‘scorched earth’), natural calamity struck a blow in the form of a cyclone that hit the coastal regions on October 16, causing massive devastation to the two subdivisions where resistance had been most firm.

With the destruction of several villages and the consequent loss of lives, the worst effect was felt on the paddy crop.

‘Before the cyclone, Midnapore had been a surplus district, exporting large amounts of paddy and rice. But, just as the winter crop was maturing the cyclone changed Midnapore into a deficit district with very limited local supplies. A troubling crop disease broke out at the same time ruining much of the paddy that had survived the cyclone.’

Yet, this was not the entire story. Studies reveal the orchestrated man-made nature of the famine. While the account above appears to be a classic example that could be explained by the ‘food availability decline’ principle (as the Famine Inquiry Commission had done), Dr. Amartya Sen in an illuminating analysis2 has argued against this theory with statistical data to prove that despite the cyclone the yield in crop in Bengal in 1943 had actually been more than that of 1941 which was a non-famine year.

‘In one sense saying that the famine was ‘man-made’ (manusyosristo) asserts, quite rightly, that Nature was not to blame – no drought, flood or crop failure caused a shortage of rice so great as to make widespread starvation inevitable … In another, more pointed sense, the epithet “manmade” expresses the conviction that greed and maladministration were responsible for unnecessary hunger, suffering and death … While pronouncing the famine man-made is not irrational, it is clearly a mistake to attribute it to the malefic actions of a few. The causes of the famine were complex and it scants the evidence to grant responsibility to particular persons.’

The freezing of supplies for the war-front, and the greed of the stock-hoarders, coupled with a general maladministration to form the primary causes for the immense suffering and the numerous deaths. Eyewitness accounts from those who actually passed through the trying times reveal the social disruption that resulted, most notably in women taking recourse to prostitution for subsistence.4 There are also evidential records of separation of family members, abandonment, sale and abuse of children.5 Also on the increase was the number of people who had turned into beggars, marked by a general lack of violence, and no major report of food rioting or insurrection in response to the acute starvation. However, scholars mention that Congress rebels in Midnapore who did not have the political inhibitions of the Communists (the ‘peoples’ war’ policy) pushed hard to mobilise antagonism against the government and landlords, with the underground publication Biplabi openly advocating ‘attacks on landlords and big tenants’.

|

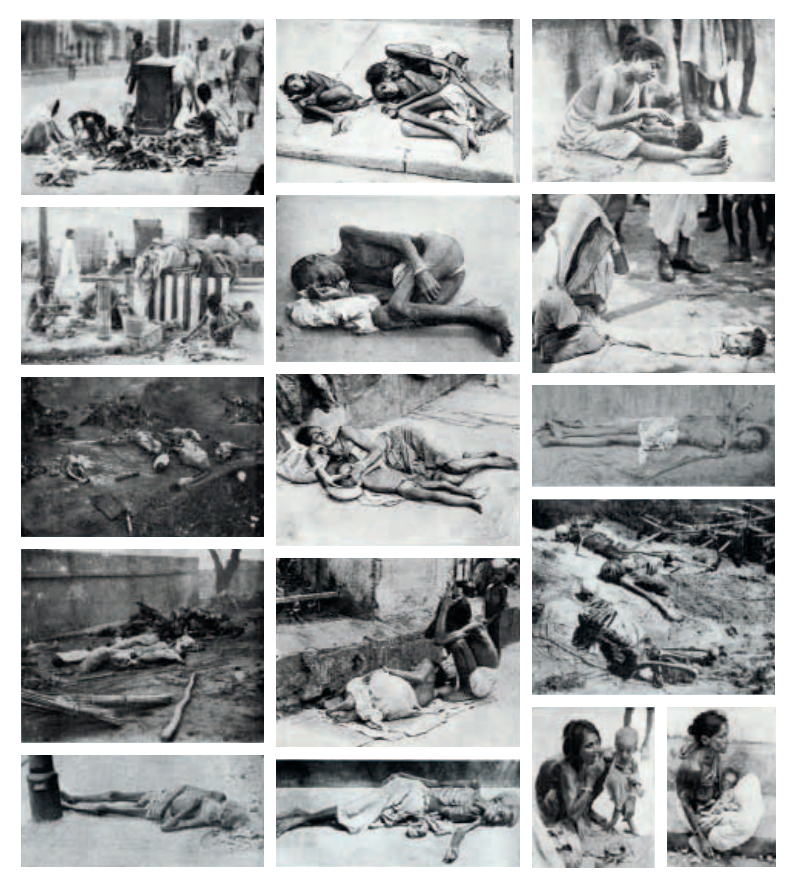

Photographs orignally published in Kali Charan Ghosh’s Famines in Bengal/1770-1943, Indian Associated Publishing Co.Ltd., 8-C, Ramanath Majumdar Street, Kolkata, First edition June 1944 |

Despite such exhortation, the result was hardly inspiring, and the pattern of response has a distinct uniqueness.

‘Mendicancy, cries and wails, imploring gestures, the exhibiting of dead or dying children — all were part of the destitutes’ attempts to evoke charity and to transfer responsibility for their nurture to new “destined providers”…Throwing themselves in the path of those who visited these shops, starving victims ensnared well-to-do strangers in nets of reproach.

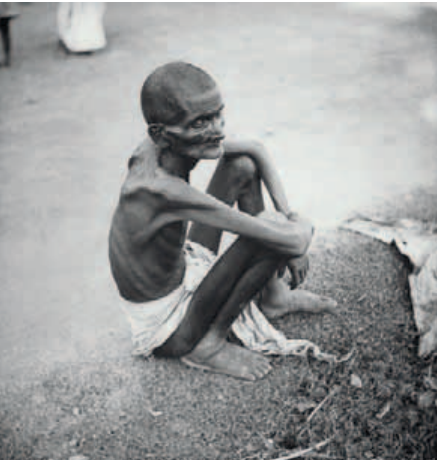

William Vandivert: A living skeleton suffering from hunger during the famine 31 Dec 1942 Image Courtesy: Time Life Pictures, Getty Image

FAMINE IN BENGAL

British Pathe

Watch a video made as an appeal for help during the famine from the archives of the British Pathe. Notice the archival notes to find insights about the way these videos were often catalogued, for example the language is noted as “possibly Hindustani”.

What language do you think the voice over is actually in?

Sunil Janah Photographs

ISSUU

Sunil Janah, like Chittaprosad, was also a member of the Communist Party of India (CPI), and an artist who travelled across Bengal capturing scenes of the famine on his camera.

Browse through some of his photographs in this exhibition catalogue curated by Ram Rahman.

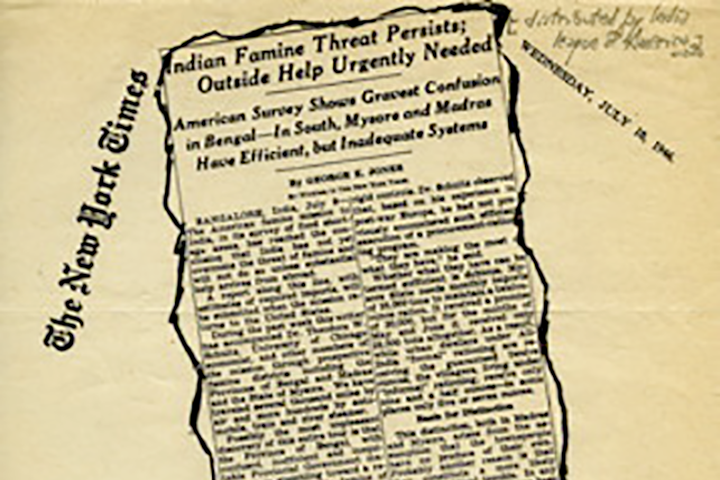

Indian Famine Threat Persists; Outside Help Urgently Needed

The New York Times

How were Indians outside India, or members of the diasporic community, reacting to the famine? This 1946 New York Times article gives us a glimpse at the diasporic Indian community’s response.

Presented by