The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

Diana Campbell, the curator, with Nadia Samdani the founder (image courtesy: Dhaka Art Summit)

Diana Campbell is the Artistic Director of the Samdani Art Foundation and chief curator of the prestigious Dhaka Art Summit, whose sixth edition starts on 3 February 2023.

She spoke with the DAG Journal’s editorial team to discuss her curatorial process and how she makes room for experimentation, while unpacking the intriguing thematic of this new edition: ‘flood’, or bonna.

Q. We are a few days away from the opening of the Dhaka Art Summit, could you give us a sense of the activity behind the scenes in the lead up to the festival?

Diana: The Summit always takes place at the Shilpakala Academy in Dhaka, which is a bit like the Lalit Kala Akademi in New Delhi, and has sister academies spread across Bangladesh. It’s been a challenge because the building has been a construction site for the last three years. So, just imagine scaffolding everywhere. Not knowing what the building's going to look like, not knowing what we can give the artists has meant that we are dealing with a lot of uncertainty in this edition, but I think it also means that a lot of the artists got very creative and were oriented towards solving problems.

DAS 2020, Héctor Zamora, ‘Movimientos Emisores de Existencia (Existence-emitting Movements)’, 2019-2020. Performative action with women and terracotta vessels, Courtesy of the artist and Labor. Photo: Randhir Singh

Q. Could you speak a bit about the foundation that supports the summit and how do you see it relating to the city of Dhaka?

Diana: The Summit is run by the Samdani Art Foundation, which was started by Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani. And I think what's very special about this is that they're not trying to be curators; they really see their role as facilitators and hosts because they love Bangladesh. While I'm an American, this is really a Bangladeshi project. Most of the team is Bangladeshi, most of the artists are Bangladeshi. And as someone who's been working there for ten years, I can tell you how dynamic the city of Dhaka is. The fact that you have so many repeat visitors every time makes this unlike other fairs or biennales, because Dhaka is an intense city. It's one of the most densely populated cities in the world. You're going because of this opportunity to have a unique experience with art and culture. It’s an international show that is rooted in the city, by which I mean that we consciously chose projects that responded to the city space and makes it essential to see them on site, instead of online or in another part of the world.

Bangladesh is a great place to experiment and do something new. The summit could be done for much less money, and much less stress if we just took works that existed elsewhere and brought them to Bangladesh, but then it wouldn't be the summit.

We are really excited about this project with a British sculptor, Antony Gormley. He studied in India for about four years before he went to art school in the 1970s. And he hasn't been back to the region since 1974. He's making a massive sculpture out of a two-and-a-half-kilometer line of bamboo that's going be moulded into this curving and spiralling energy field. But that meant for the last eight months we have been testing with bamboo artisans in villages to see what the capabilities of bamboo are. Gormley would not have been able to do this work in Paris, London, or in New York, so we really want Dhaka to become a place that adds to the work in some way. Or if we're shipping a work that already exists, there has to be a reason why this is showing in Bangladesh.

DAS 2023, Ashfika Rahman, Nochmals, 2019, Experimental film photograph. Courtesy of the artist and Dhaka Art Summit

Q. And what are some of the logistical challenges around your work?

Diana: It requires constant problem solving. For instance, there's an artist who is making work from different jute factories and one of the twill machines broke down, so what do we do? Problems like this crop up all the time. Making sure all shipments are able to clear customs in time and coordinating with different time zones, different holidays and travel regulations.

There is a beautiful performance by Roman Ondák, which is called Teaching to Walk, where it's a mother in the gallery teaching her young child how to walk their first steps, but we had to find people six months ago who had four-month-old infants, and ask them if they are going to be free! So it's casting, producing and shipping. And Nadia is involved in the department of hosting—making sure everyone knows the schedule and feels welcome—which is also a part of the process. Communicating with 150 artists on an almost daily basis requires a lot of coordinated work. And then the team moved into the venue on the 16th of January, so facilitating that is another process that is going to start soon.

I’m also interested in problems of translation. I'm very critical of shows that are made in a place where English isn't the majority language but the texts are just in English. So we make sure everything is in English and in Bangla.

DAS 2020, William Forsythe, ‘Fact of Matter’, 2009, Polycarbonate rings, polyester belts, ground support rigging. Courtesy of the artist. Presented with additional support from ifa | Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen and the EMK Center. The development and international exhibition of Choreographic Objects by William Forsythe is made possible with the generous support of Susanne Klatten. Photo: Randhir Singh.

Q. We just wanted to probe you a little bit about the theme of the Summit, which is ‘Bonna’, a word that has a wide variety of connotations associated with it. Would you say that these floods are simply to be resisted? Or do they need to be re-read or curated in a different way?

Diana: Yeah, I think what's interesting is that you wouldn't name your child ‘forest fire’ or ‘earthquake’. So if you're naming your child ‘bonna’ there, it's not only a negative connotation, but also a question that opens up a lot of curious spaces of inquiry. Bonna is a character, even though you are not going to see her or she's not going to have a form, but she is a character in the Summit who is asking questions. And one of the questions is, “Would you still name your kid Bonna?” Does it mean the same thing now as it did earlier? And the summit will also try to be silly on occasion; perhaps suggesting Bonna to be this silly little girl too. I think that's also an entry point to talk about serious stuff.

So yes, I think it's complex and connotes many things. It is about climate change, but it's also asking us, “How do we weather that?” Because it's a reality and it's not going away. So we are learning from those coping strategies and finding ways to be more solution-oriented. We are also asking how climate is carried into cultural work and memory. Variability was a part of life and learning how to live with water and boats, almost amphibiously, was part of the culture. Cultural archives held in songs and stories can often help you trace these shifts in climate as well as human responses to climate change. So I think it is about forming contextual attitudes. And we wanted to address that.

I'm also trying to be as climatically responsible as I can. There are certain kinds of works that could be justified on thematic grounds, but not in terms of the carbon footprint it would extract.

Q: You've quoted Lesley Lokko to say when “you're in the eye of the storm, it's often the right point to push for maximum change”. How does your curation relate to principles of using artists’ activism around social and communal spaces, especially during times of emergency or extremes? Is that an objective you have in mind?

Diana: Yes I do, which is why I think it would be very difficult for me to have a traditional museum job. I like to work with art that can do something. But it's not like all art has to do something. Art can also just touch you, a beautiful painting can touch you, and it's not that we don't have beautiful paintings, we have lots of them in this show! But, you know, there should be a reason why it's there. And I think art is incredible in how it can make you see things differently. It can help you connect, it's a shared human experience.

And I like that line in the text that is asking, “How do you tell a story of multiple crises while facilitating hope?” We want this to be hopeful. We all come from different contexts and go through hard periods, but it's important that we learn from history together.

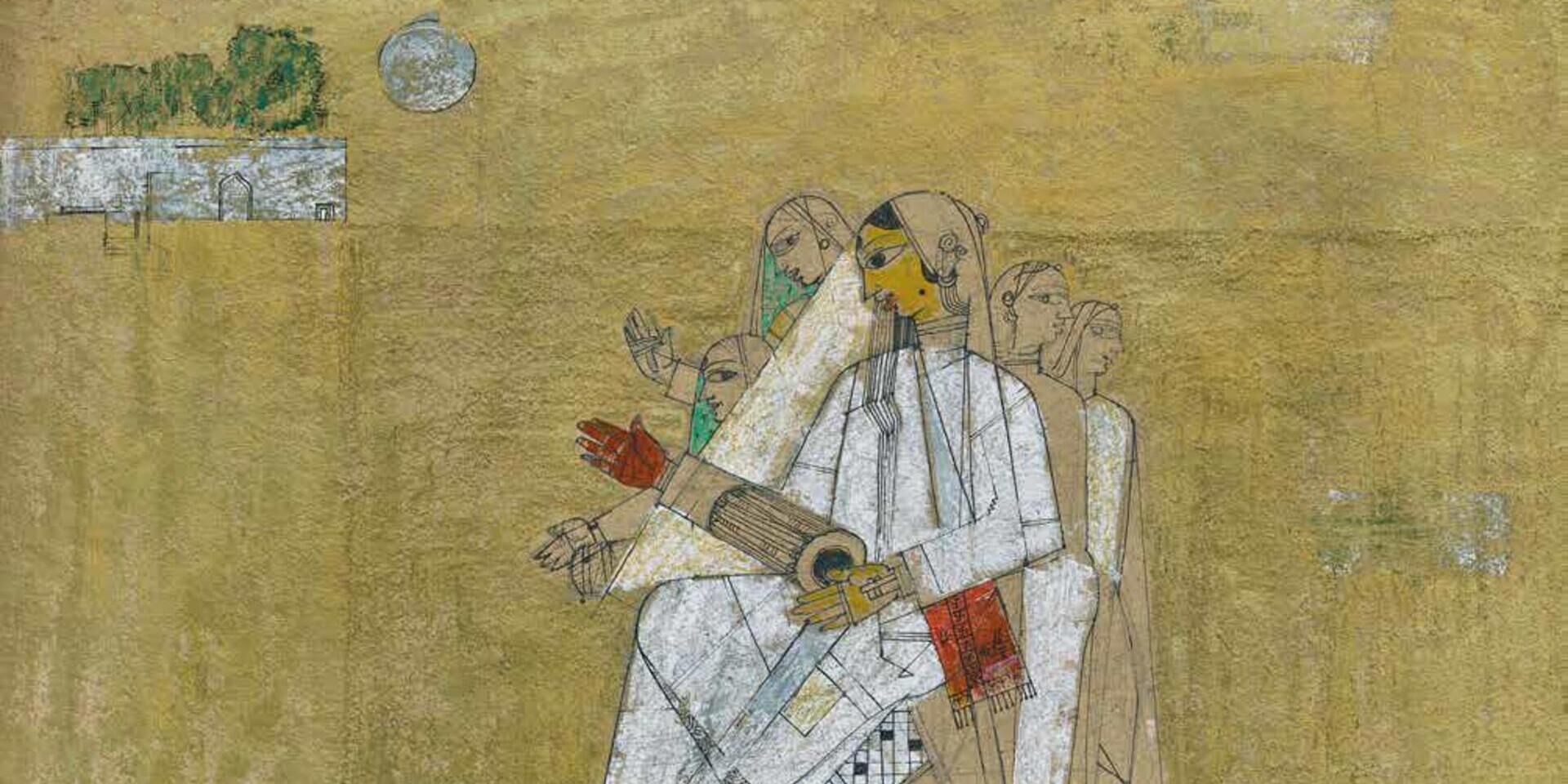

DAS 2023,Salman Toor, Illustration for Amitav Ghosh’s Jungle-nama, 2021. Courtesy of the artist, author, Harper Collins and Dhaka Art Summit

Q. How do you balance the mix between preserving a clear, curatorial theme or vision while remaining aware of the need to platform new work, new voices—those especially that are trying to respond to contemporary events and the present moment?

Diana: My practice involves looking at art all the time. And the theme emerges from the art that I'm seeing, so it's not like I just decide the theme in advance and then find things to fit that. So yes, they go together and the themes are developed from looking at art and from being in constant dialogue with artists. So that keeps me in dialogue with young artists as well. It is the part that gives me the most joy—to provide a platform for people who haven't had this kind of stage before.

Things can be too literal if you just have this idea and then you're looking for things to illustrate it. So that's why I love this thing because it's so complex. I love themes that are so open-ended, but also very coherent so you can see Bonna as the little girl, you can see Bonna the flood, you can see Bonna the mistranslation, you can see Bonna the deluge of information—there’s just so many different ways to look at it and I think in a way you could, depending on how you want to interpret or not you could experience many different shows within the same show.

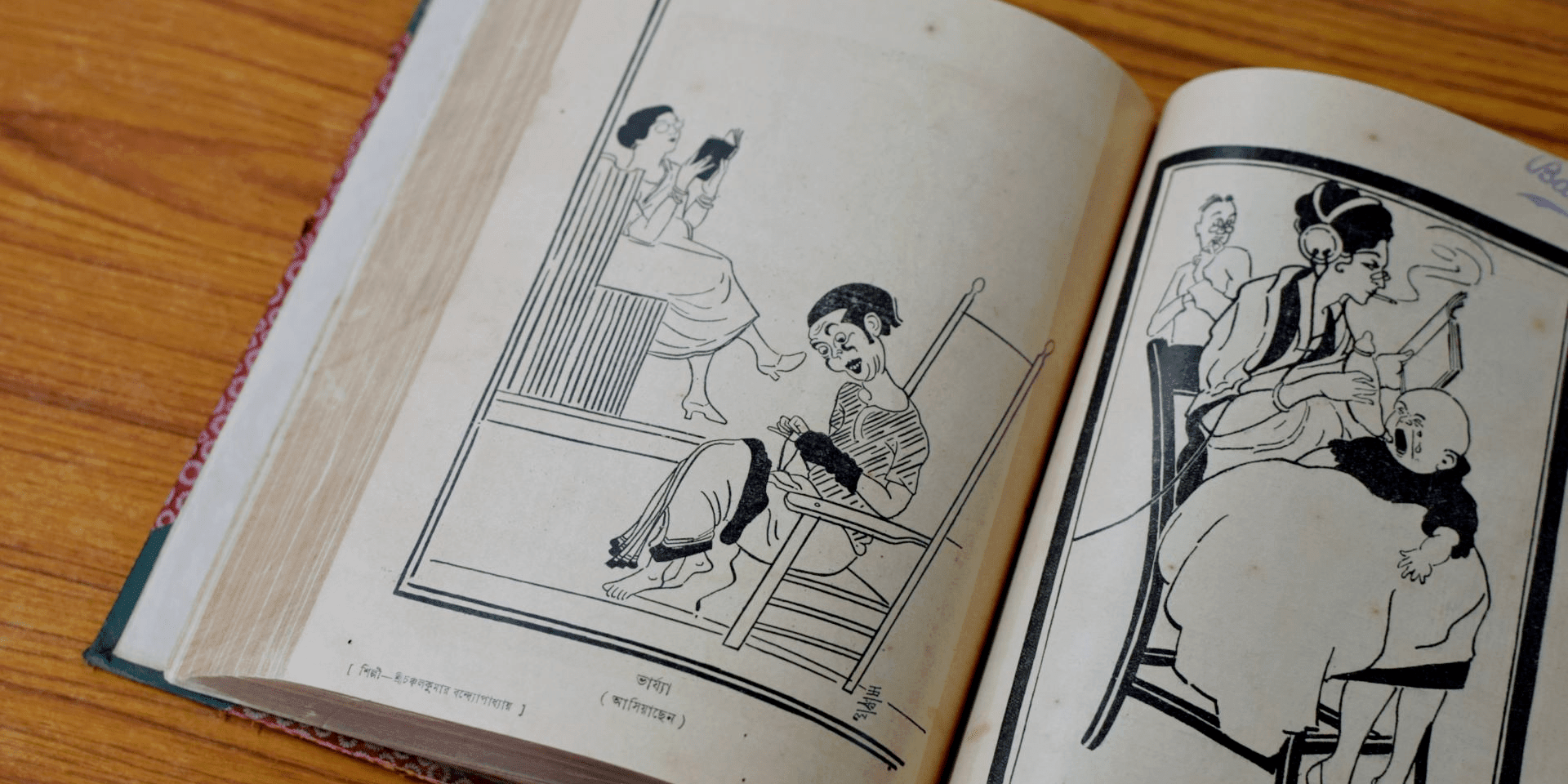

Q. As a research platform the Summit also places importance on intergenerational dialogue, which is a shared area of interest for DAG as we build engagement around our historic collection. This year you are showing works by Chittaprosad from the DAG collection at the Summit. Why is the intersection of the past and the present important to you?

Diana: While this Summit is a forward-looking entity, we also want to look back because we realize that there are holes in people's knowledge of the past. And we want to play that role, because if somebody has an educational platform, we want to be able to fill in backwards, if that makes sense. And I think there's a lot to learn. Chittaprosad is a part of a special exhibition co-curated by Akanksha Rastogi, Ruxmini Choudhury and myself and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art called Very Small Feelings, which conceptually follows the artist’s prompt to ‘tell a story’. It is a platform to highlight personal and collective narratives. It will bring together voices from Bangladesh, India and the global diaspora, inviting artists to draw on the power of telling and retelling stories. It will feature works by artists like Joydeb Roaja, for instance, which will revisit his traumatic childhood memories growing up in the Tripura community from the Chittagong Hill Tracts, seeing army boot prints on the hills and tanks haunting his dreams. We see these inter-generational dialogues as being essential to the work that the summit tries to do, and I think it is necessary to have this sense of the past if we are going to think of the future as well.

|

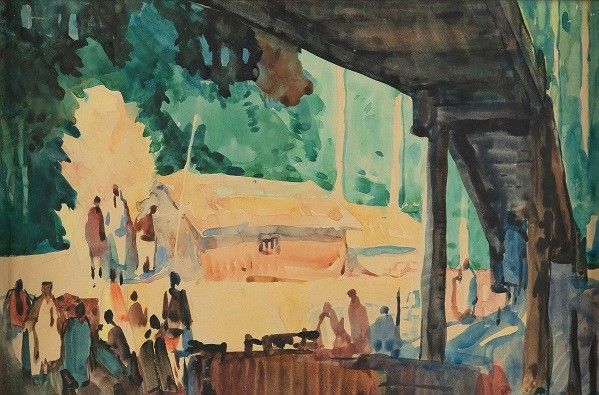

DAS 2023, Joydeb Roaja, Submersible Dream 1, Submersible Dream 2, 2022. Pen on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Dhaka Art Summit, 2023 |

Q. A personal question to end with—you started working on this summit ten years ago, when you were in your 20s. What surprises you about the journey you’ve made so far?

Diana: I joke with some friends and call it youthful idiocy (laughs). Now, after all this experience, I can tell you exactly why we do certain things and not others, but it also takes a lot of learning by doing. So I think the journey is important and you are learning as you are going and I think the challenge is how not to lose that youthful idiocy as you get older. You can't be afraid to try new things or just because something was so difficult last time. But you do know when something is impossible. Like I can't make mud dry in five days if it needs fifteen days. So, certain things you can't change but I want to cultivate the bravery to try new things and not to get scared because something's difficult; and that's something that I always try to impart to my team. I think it is important not to get lazy, to stay curious and learn iteratively. I also feel really happy to get something started from scratch. And when you start something from scratch, it is sometimes easier than to fix a big broken structure.

Know more about the Dhaka Art Summit.

’Conversations with Friends’ is a series where we speak with inspirational figures from the art world who are working behind the scenes

related articles

Essays on Art

Before the Chaos of Destruction: Jeram Patel's Iconic Works

Roobina Karode

February 01, 2023

Intersections

The Painters’ Camera: Husain and Mehta's Moving Images

Term of the Month: The Artist’s Village

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

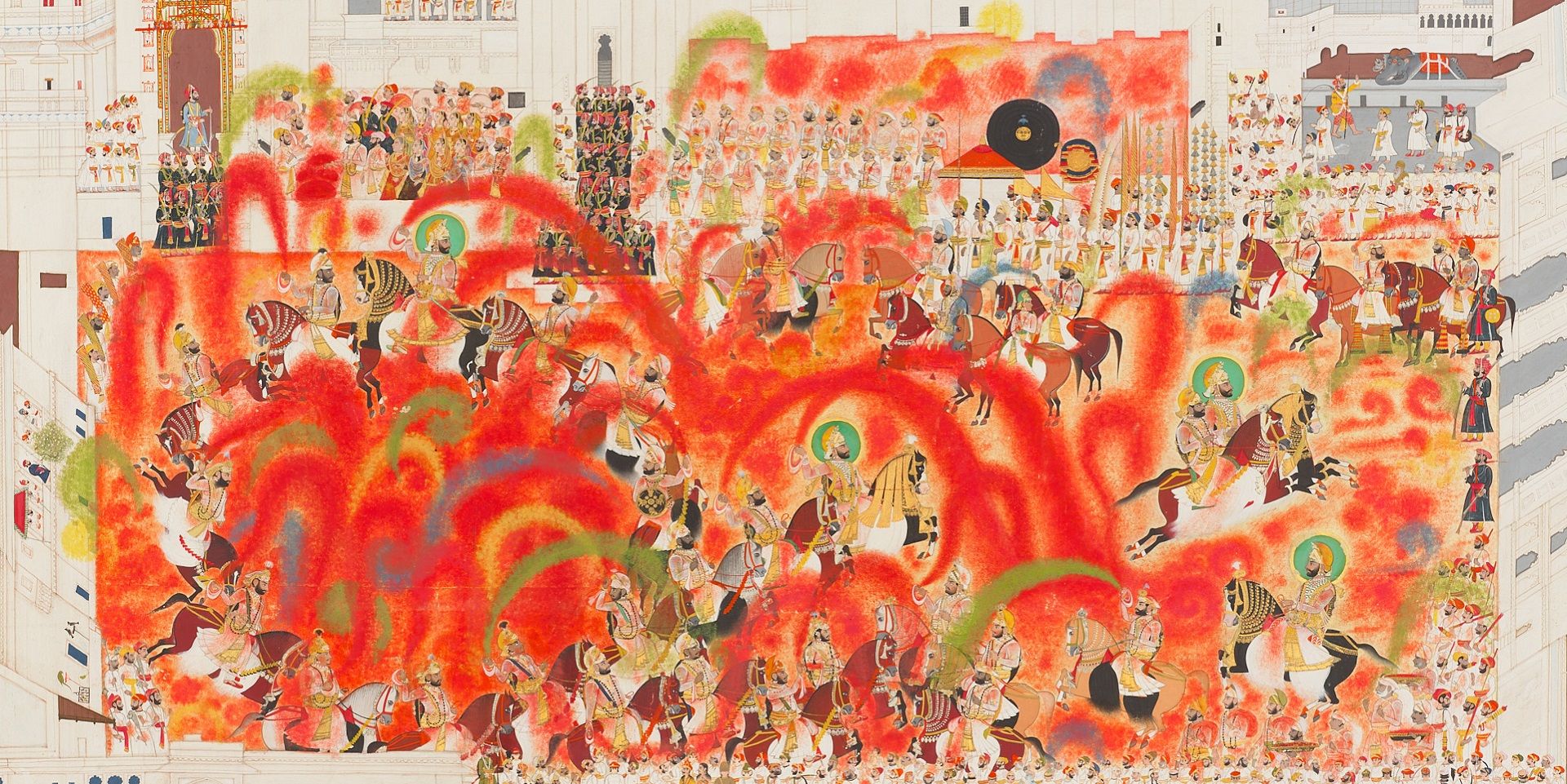

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023