On Collecting Textiles with Uthra Rajgopal

On Collecting Textiles with Uthra Rajgopal

On Collecting Textiles with Uthra Rajgopal

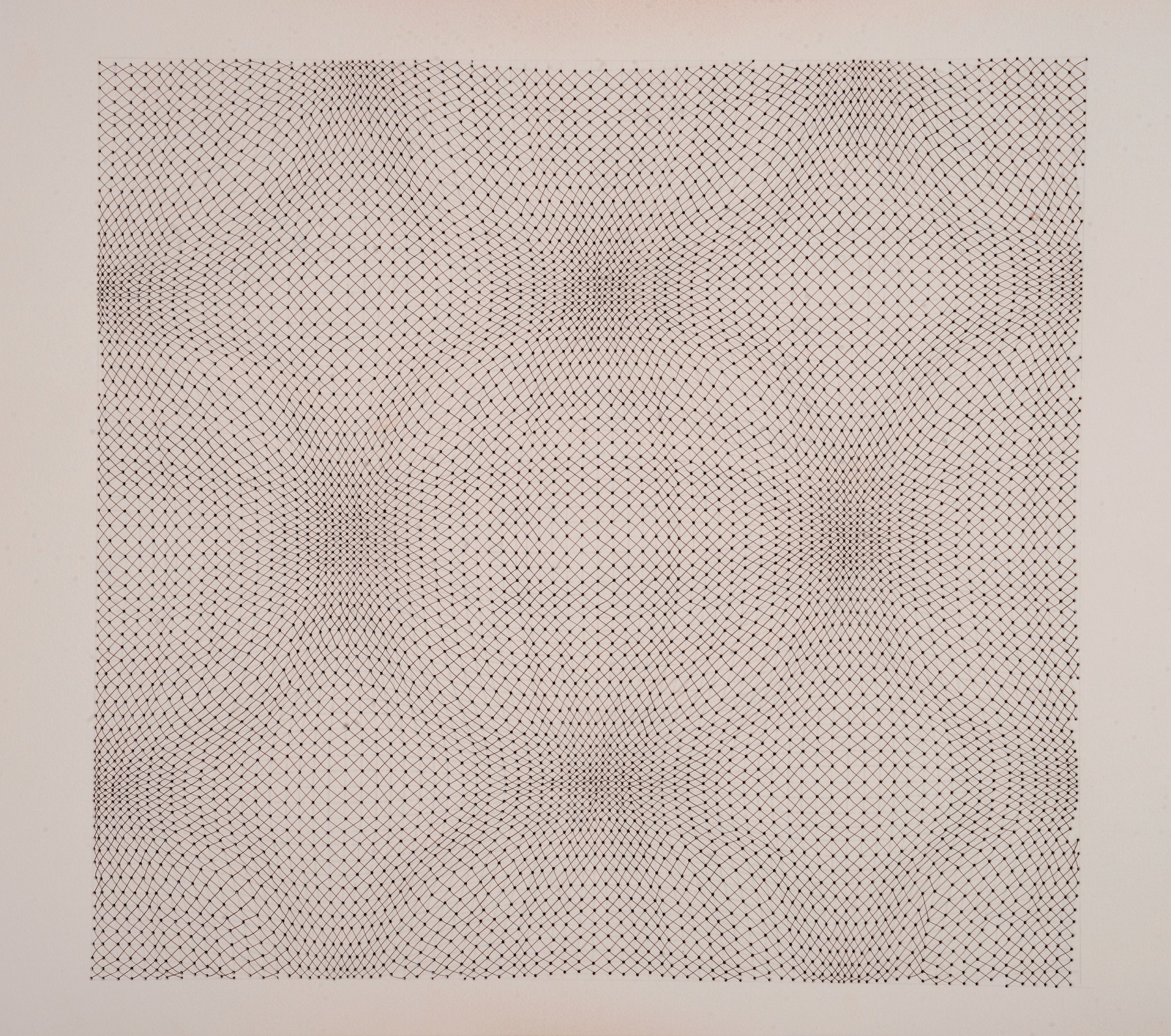

Bharti Parmar, Corona Virus in Black and White (detail), Embroidery Diptych, 2020-21. Image courtesy: Uthra Rajgopal and the artist

Are the histories of art and fashion distinct from each other? Even a cursory glimpse at the contemporary art landscape—on view during occasions such as the India Art Fair, 2023—tells us otherwise. Fabrics, textiles and weaving practices are being increasingly incorporated into the body of works produced by artists today.

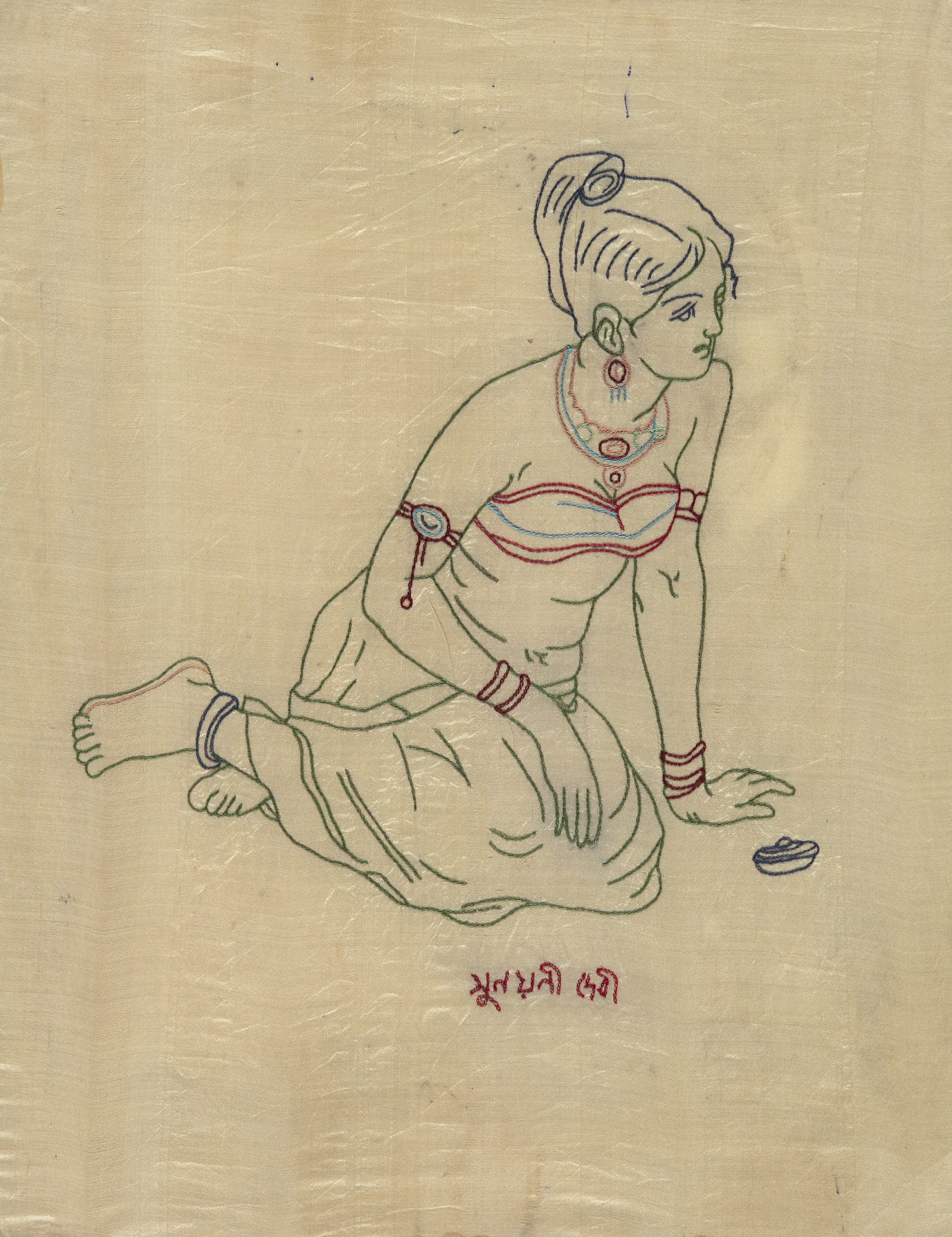

They bring with them a host of connotations, historical narratives and sensorial memories that working with other media does not. Modern artists in South Asia have used textiles as direct influences on their work—especially women artists such as Sunayani Devi—signalling their importance as sources of formal innovation, design, textural variety and as a living artisanal craft-making practice. In order to understand this landscape better, especially from the point of view of curators and collectors, we spoke to someone who knew about the lay of the land intimately through her own extensive practices of curation and advising on collections.

Uthra Rajgopal is the Assistant Curator for Textiles and Wallpaper at the Whitworth, the University of Manchester, which is building a collection of contemporary textile artworks made by women artists of South Asian descent living in England. Her work involves curating textile exhibitions and advising museum collections on dress and textile works. In 2019, she received the Art Fund New Collecting Award, which is aimed at supporting the Whitworth acquire South Asian textile works by contemporary female artists. She spoke with DAG briefly on the practice of collecting textiles for museums, their historical significance as artworks as well as trading commodities from South Asia, and how contemporary artists are responding to this complex colonial legacy through their own work.

Suman Gujral, All my Sorrows, Cotton handkerchief, silver print making powder, midnight blue printmaker’s ink. Image courtesy: Michael Pollard for the Whitworth, the University of Manchester and the artist.

Q. I was curious about how institutions are shaping or influencing collecting practices. Now, you have won the Art Fund New Collecting Award in 2019, which was intended to encourage the collection of art works connecting South Asia and the diaspora in England. How does this award and its brief respond to your curatorial or collecting instincts?

Uthra: So, the Art Fund New Collecting Award is a unique award that’s granted by the Art Fund in the UK for UK-based curators. And they are particularly interested to hear from curators who have not had the opportunity to make acquisitions for their respective museums.

As a relative newcomer to the scene, I had realised that in Manchester whilst there was a significant South Asian textile collection, and the previous collectors had made acquisitions relating to contemporary textile art mainly from European and western artists, there wasn’t enough being done to level the playing field for South Asian contemporary textile artworks. And having been a regular visitor over the last four years or so to the India Art Fair and going to the Biennales in South Asia, I recognised that there is such a vibrant scene here that it is challenging our perception of what South Asian textiles were, what they are and what they can do in terms of contemporary art.

So I put in a proposal to build a collection featuring women artists from South Asia and from the diaspora. Firstly, because I felt that women were underrepresented in the field of contemporary art. So I wanted that, and I also wanted to make sure that these people were named, that women were named, because too many textiles, too many South Asian textiles are in museum collections with no provenance details, including the identity of the makers.

Secondly, with the diaspora, there wasn’t anything being done in terms of making acquisitions and getting their voice and identities heard and seen in the Whitworth collection, which is in Manchester. And I felt overall, in the UK there was still very little being done for the South Asian diaspora. And you’ve got to remember that the South Asian diaspora have a very particular view of South Asian culture through our parents, through our grandparents. And what I found was that there was a gap between the way the diaspora remembered, connected with South Asian ideas of home and identity, and the way contemporary society is moving in South Asia. And I felt that by building a collection we could at least start to create and generate a conversation between the two communities.

And also to open up those conversations from within the communities, because I’m tired of people from outside our communities telling me and telling us how South Asians are and what they do and what they produce. And I feel that the best people to tell the story is always the respective community because that narrative and that point of view is so much more nuanced and powerful when it comes from within, rather than an external voice trying to learn something through a handful of experiences or exhibitions or meeting people.

Rehana Mangi,Untitled, 2020, Human hair on archival paper. Image courtesy: Michael Pollard for the Whitworth, the University of Manchester and the artist.

Q. How do you think the relationship between textiles and modern or contemporary art practices has evolved for South Asian artists? And how have they come to activate traditional art practices like painting or sculpture?

Uthra: I think textiles have become more prominent as a media in contemporary and textile art forms because you are seeing a really exciting expansion and interpretation of textile through different practices -- whether through performance art, sculpture, or site-specific installations. Since South Asia has this great tradition and knowledge that we have all grown up with, these artists are seeing these textiles--and they can be everyday textiles, not necessarily the museum-quality textiles that have survived for hundreds of years that nobody wore or were collected because they were highly prized-- in ways that connect to the issues and politics of our lives, and the social construct that we live in, and the challenges that we face today.

Madi Acharya-Baskerville is one such artist who uses found plastic from the shoreline and combines that with hand-me-down shawls and saris from her mother’s wardrobe that she cuts up and uses to build these fantastic sculptures to talk about environmental change, but also displacement and migration and how those histories are embedded within textiles. So I think those layered voices can come through really well.

So that personal relationship that South Asians have with textiles can sometimes make it a lot less intimidating (medium) than an oil painting or a water colour, because it has that aspect of making something with your hands which comes from your land, that is being grown and spun and woven. Somehow, we all have a more ready connection with that. It’s not something that goes on in an art school, where you have to learn or you have to train formally. We can all relate to cloth—we touch it, feel it and smell it. All of these sensory experiences help us to connect with contemporary art pieces that use textiles in a way that is, I feel, much more profound than traditional art works that we see.

Madi Acharya-Baskerville, Here to Stay, 2019, the first in the series ‘Unnatural Selection’. Sculpture Found plastic, textiles, kapok, chicken wire, papier mâché. Image courtesy: Michael Pollard for the Whitworth, the University of Manchester and the artist.

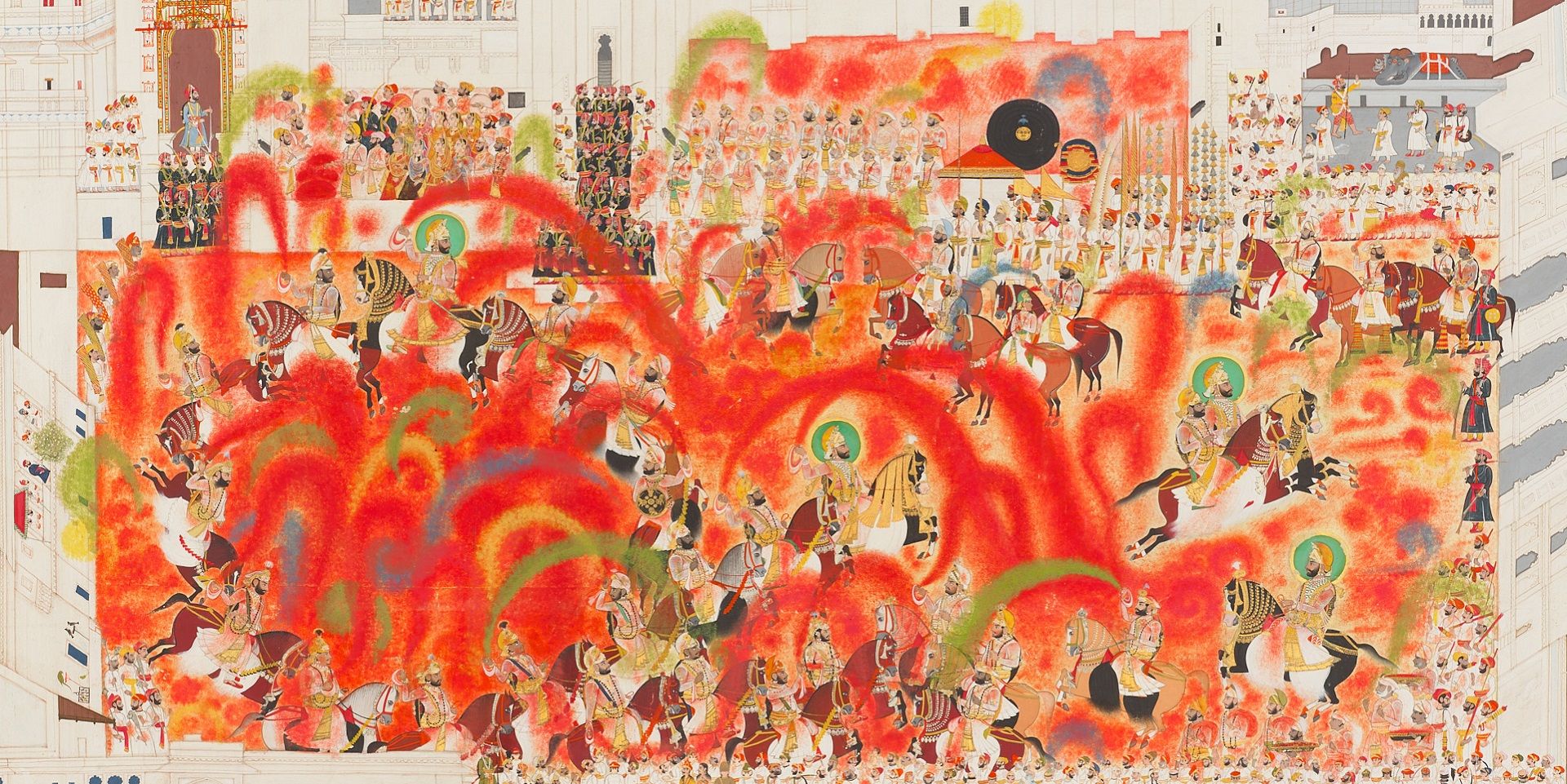

Q. Considering the artists whose works you have curated, such as Yasmin Jahan Nupur or Madi Acharya-Baskerville—how do you think they respond in their work to these very loaded histories of collecting textiles as commodities, as a prime colonial trade object? What are their takes on these histories?

Uthra: Yasmin Jahan Nupur is very interested in bringing the darker histories of colonialism to the surface. We read a lot about the East India Company and the way they dominated the production of muslin in Dhaka. And what Yasmin is interested in is looking at the reality of that exploitation, and the undercurrent and the impact of that level of dominance on the communities, and how it affected the land and the art form itself. With Madi, I think there’s a different angle that she takes in that she is looking at ideas of displacement and migration through using textiles. And because Madi is part of the diaspora, her connection with textiles in a particular piece titled ‘Here To Stay’ speaks to the pressures that people feel when they are a minority.

And a lot of people who are from South Asia who arrived in the UK, either as a result of being expelled by Idi Amin from Uganda, or taking up jobs in mills, or like my parents who went in as part of that recruitment to service the National Health Service—the idea of them settling was always a question mark. But then, after a while they decided that they were there to stay, And ‘Here To Stay’ is a really powerful statement because a lot of people faced a lot of racism. Asians, South Asians were not made to feel welcome. It wasn’t just name-calling, it was also harassment. Your house could be graffitied on, for example, or you could be walking down the street and you could be told to go back to your own country. I’ve heard all of that personally growing up in England.

And I’m not saying that it’s a bad place or horrendous place, but there are pockets of histories that a lot of people—like my family and maybe people who were expelled from Uganda—they wouldn’t necessarily talk about the difficulties they had. Like the people who were displaced by partition, who just want to get on with their lives and actually want to forget about those painful memories.

But it now comes to a point where through contemporary art we can actually talk about these issues in a way that’s sensitive and it also helps that we’re further away in time from the event. So I feel that their approaches are very different in terms of colonialism and the impact it’s had on them and the way they position textiles in their contemporary art.

And the other artists I should tell you about who were part of the award include Arshi Irshad Ahmadzai, Rehana Mangi. There’s also Rakhi Peswani who was in the collection, Bharti Parmar, who’s from the UK, and Suman Gujral whose family were directly affected by the partition and Suman used her late father’s handkerchief that he carried with him from India to the UK to make a beautiful work. Artpro from Bangladesh also made narrative textile artwork with kantha.

And when I collected and acquired that piece I was really aware that at the Whitworth we have a lot of young audiences coming -- loads of schools. And I felt that through stitch and kantha work we had an opportunity to not only share that history about the changing seasons in Dhaka, but also that history of kantha work and how it connects to that part of the world.

There’s one particular school in Whitworth that I used to work with called Stanley Grove and 98 percent of those children were from a Bangladeshi background. So to see themselves represented in an artwork in a museum is a really great thing.

|

Rakhi Peswani, Abrasion and Erasure (damp), 2012, 50 x 50 cm, Cotton man’s handkerchief with hand embroidery. Image courtesy: Michael Pollard for the Whitworth, the University of Manchester and the artist. |

Q. There is lot of conversation around decolonising museum practices today. The museum is also seen as an institution that is engaged in classifying different art, such as painting or dresses and furnishing. So how do you think that conversation about decolonising can happen through the idea of how we approach categories of artworks, and the fact that furnished products and textiles have traditionally occupied almost an entirely different genre than what fine arts or high arts traditionally talks about, whether it is sculpture or painting?

Uthra: So the most powerful voice in the debate around decolonisation is the public—the ordinary visitor. And it’s because of the public that that pressure is now being felt in museums. And the curator sitting in a museum, however many years they’ve been there—is not the authority on everything. They must be open to a visitor’s suggestions or expectations. If there is a comments box, and perhaps a label is incorrect or it doesn’t go far enough, then please say it because this is the best way we’re going to learn. We have to learn from each other.

Often, it’s not just about the way collections have been classified, it’s also about asking what they represent. The curator normally works under a lot of pressure. They work on multiple projects and have very little time actually to sit down and do things at a granular level because they have so much to get through. And so a lot of the time there’ll be a lot of surface level writing about that particular object.

And what’s happening now in the West, particularly in England and the UK, is that departments are becoming less divisional, and they’re actually collapsing specialisms. It is essentially a cost-cutting exercise. Museums expect more work from less number of staff. And so the luxury of time of learning through the collection as a curator— going into the archives, sitting there with trays on tables is not happening—the curators themselves are not getting the time to do that.

And so, if we as visitors and people have a particular area of knowledge or expertise or have some family history or connection to Mashru or Aari embroidered work, or there’s a Jamdani or a Banaras sari, then please tell the museum, please write to the curator, write to the museum. And that way we’ll have a much more meaningful debate around decolonisation.

Artpro, Nakshi Kantha: Interwoven Dialogues ‘Rainy Season’ (2019-2020), Cotton sari with cotton embroidery. Hand embroidered. Dhaka and Jamalpur, Bangladesh. Image courtesy: Michael Pollard for the Whitworth, the University of Manchester and the artist.

|

Sunayani Devi, Untitled, Embroidered silk laid on mount board. Collection: DAG |

All images of the artworks are copyright of the artist and cannot be reprinted or reproduced without express permission.

related articles

Conversations with friends

The Making of the Dhaka Art Summit: Behind the scenes with the Curator

February 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Conscious Collecting with Asia Art Archive and Durjoy Rahman

Editorial Team

March 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Mysteries of Indian Art: A Conversation with Mamta Nainy

The Editorial Team

May 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Debra Diamond on Royal Udaipur painting at the Smithsonian

Ankan Kazi

June 01, 2023

Conversations with Friends

Imaging Water: A Conversation with the Smithsonian's Carol Huh

Ankan Kazi

July 01, 2023