Paritosh Sen and the Art of Humour in an Independent Nation

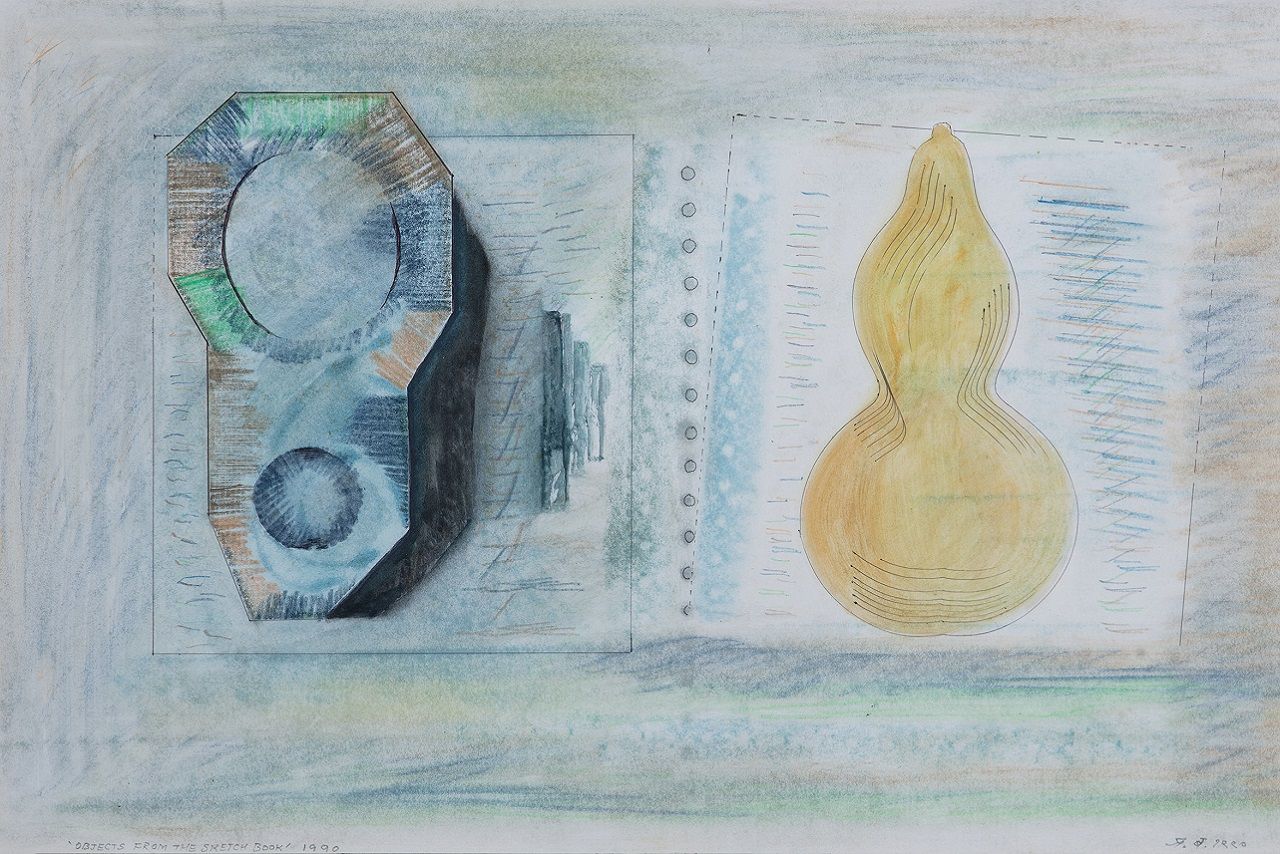

PARITOSH SEN

related articles

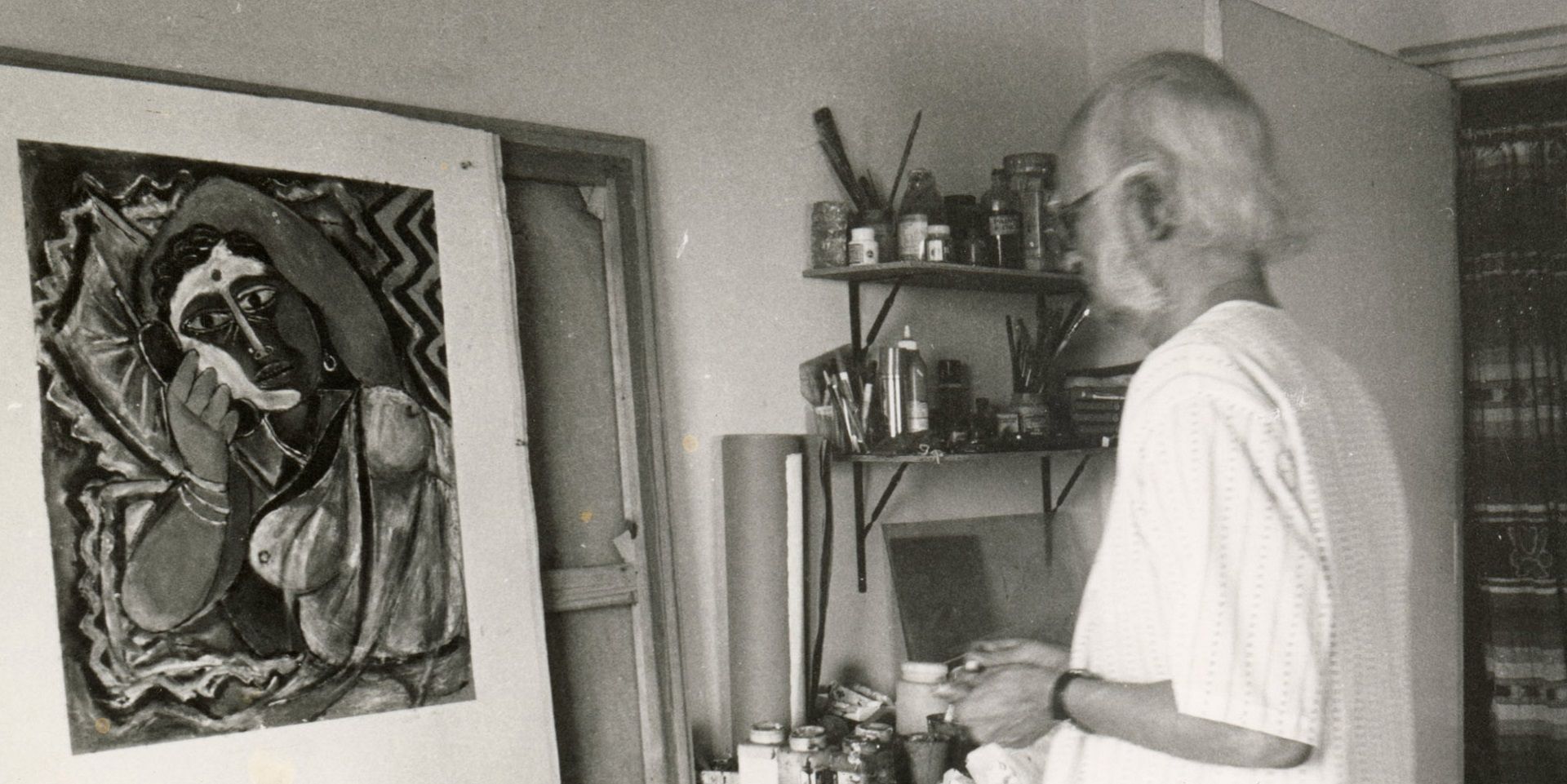

Paritosh Sen at work. Collection: DAG

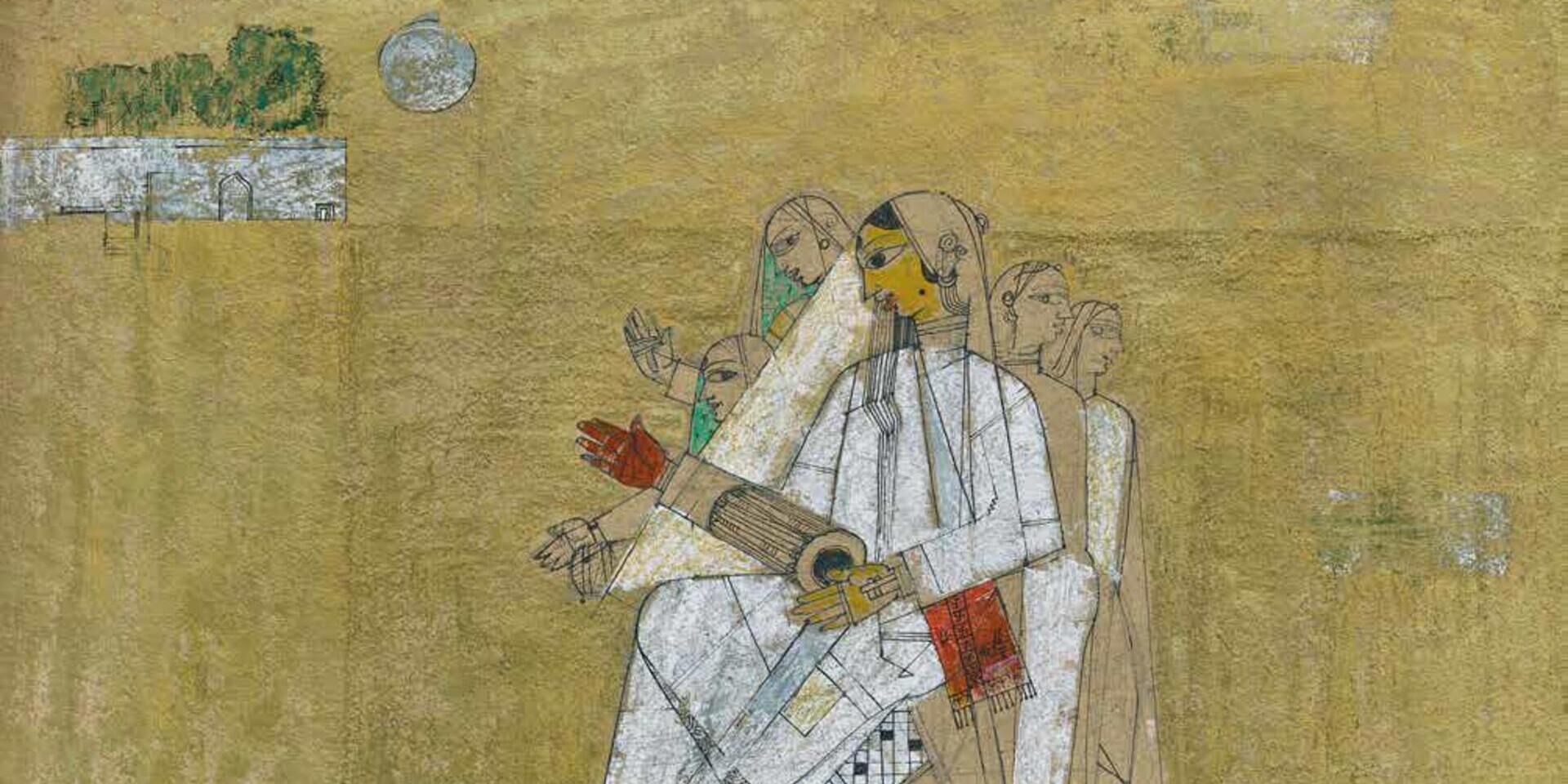

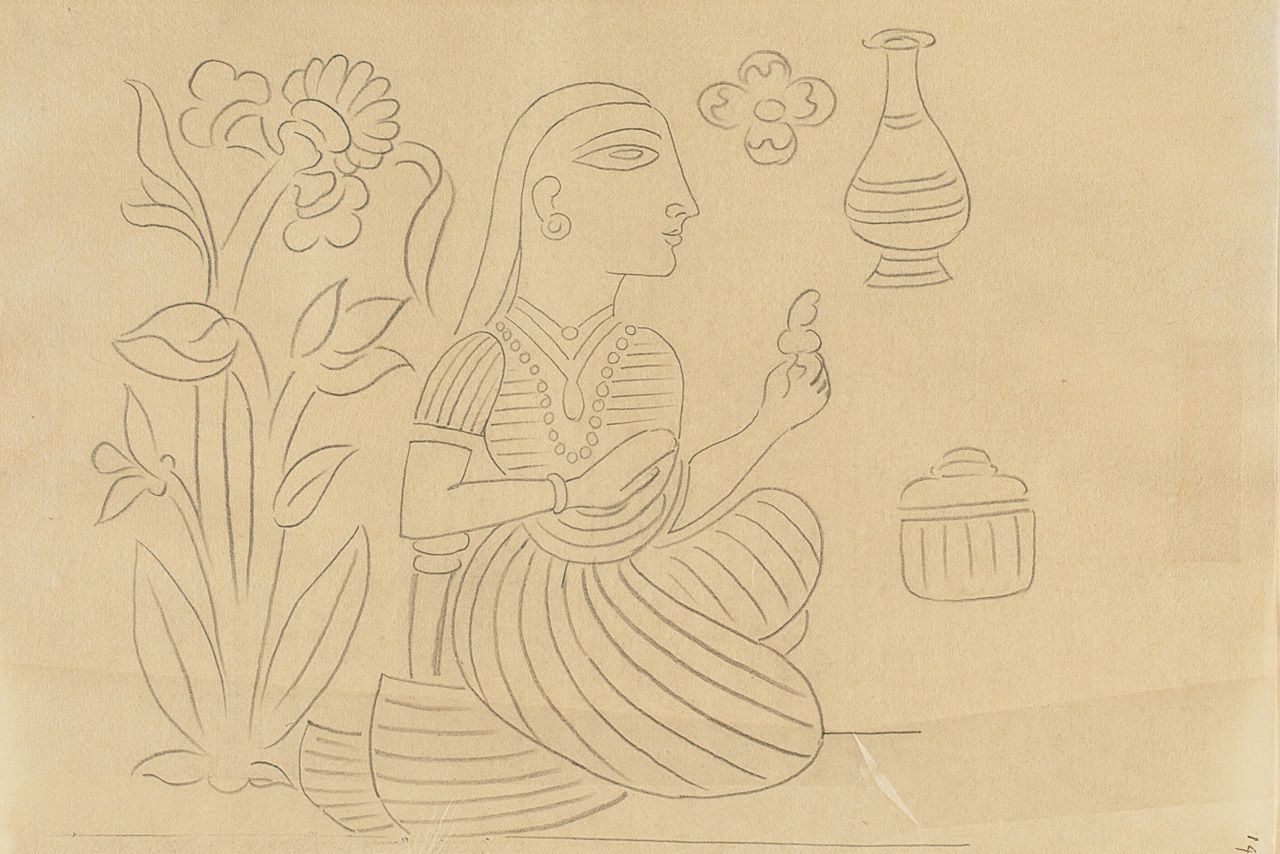

A founding member of the Calcutta Group, Paritosh Sen (1918—2008) belonged to a generation of Bengal artists who were trying to create new stylistic idioms during the height of the nationalist movement in the 1940s and the decades after independence was gained in 1947.

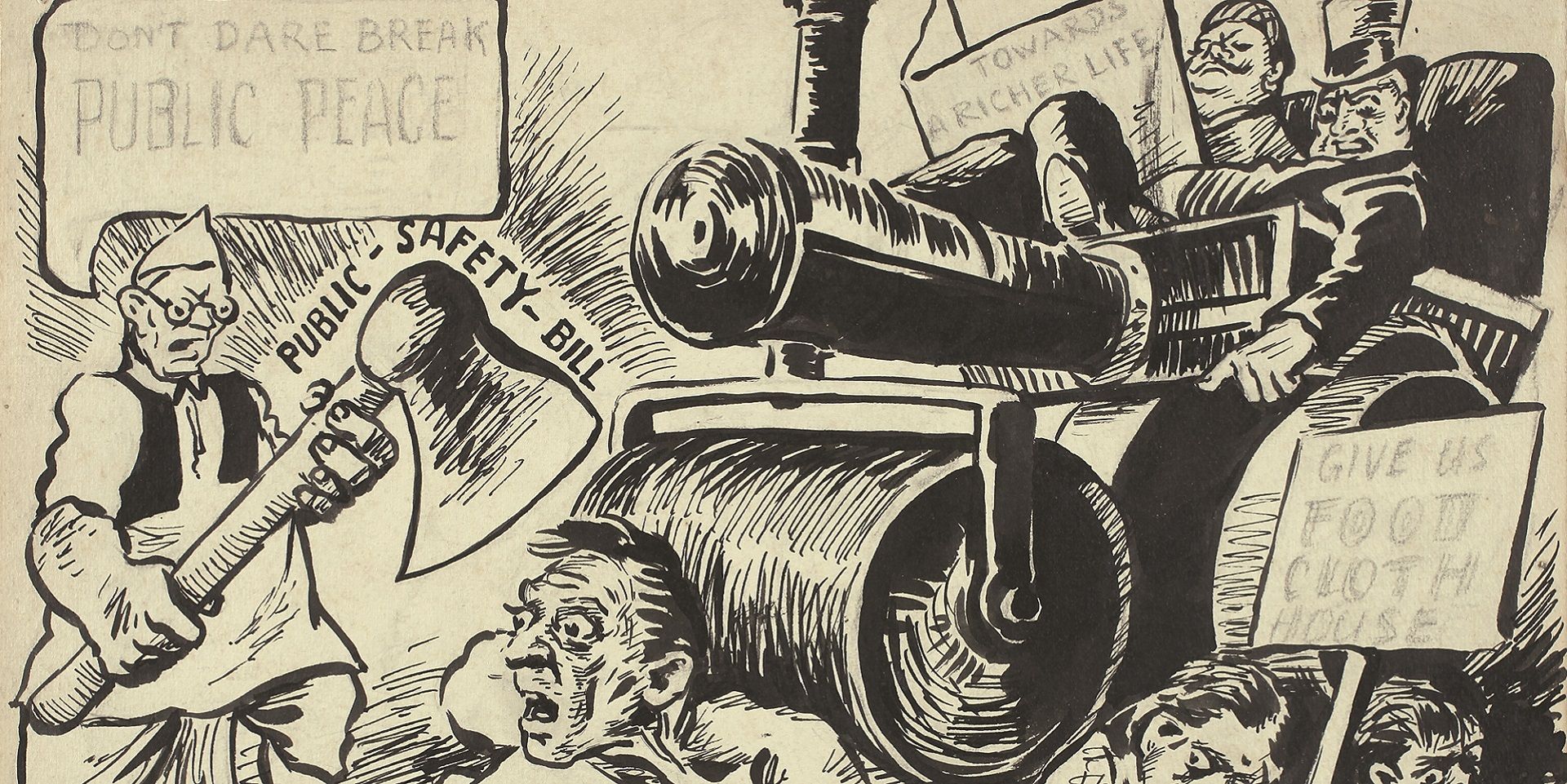

Breaking away from the revivalism of earlier artists, Sen is also known for integrating cubist modes in his modern depictions of urban life and its changing scenarios. He drew liberally from the tradition of Kalighat pats in his painting of modern life as one that is soaked in irony. Even though humorous paintings, caricatures and sketches have been made by artists like Abanindranath Tagore and Gaganendranath Tagore earlier, among many others, Sen drew a line from their comic observations of colonial-urban hypocrisy to the post-independent or postcolonial era, as newly minted Indian citizens put themselves into a twist while responding to new desires of consumption, nation-building and modernity. Again, like many other modern artists, Sen wrote regularly about his own practice, integrating his memories and life narratives into ways of making and seeing art across the world. The essay reproduced below is a new translation of his thoughts on humour, caricature and satire, which have traditionally occupied a hierarchically lower zone of critical enquiry than the more lofty themes that Sen also tackled (such as the Bengal famine).

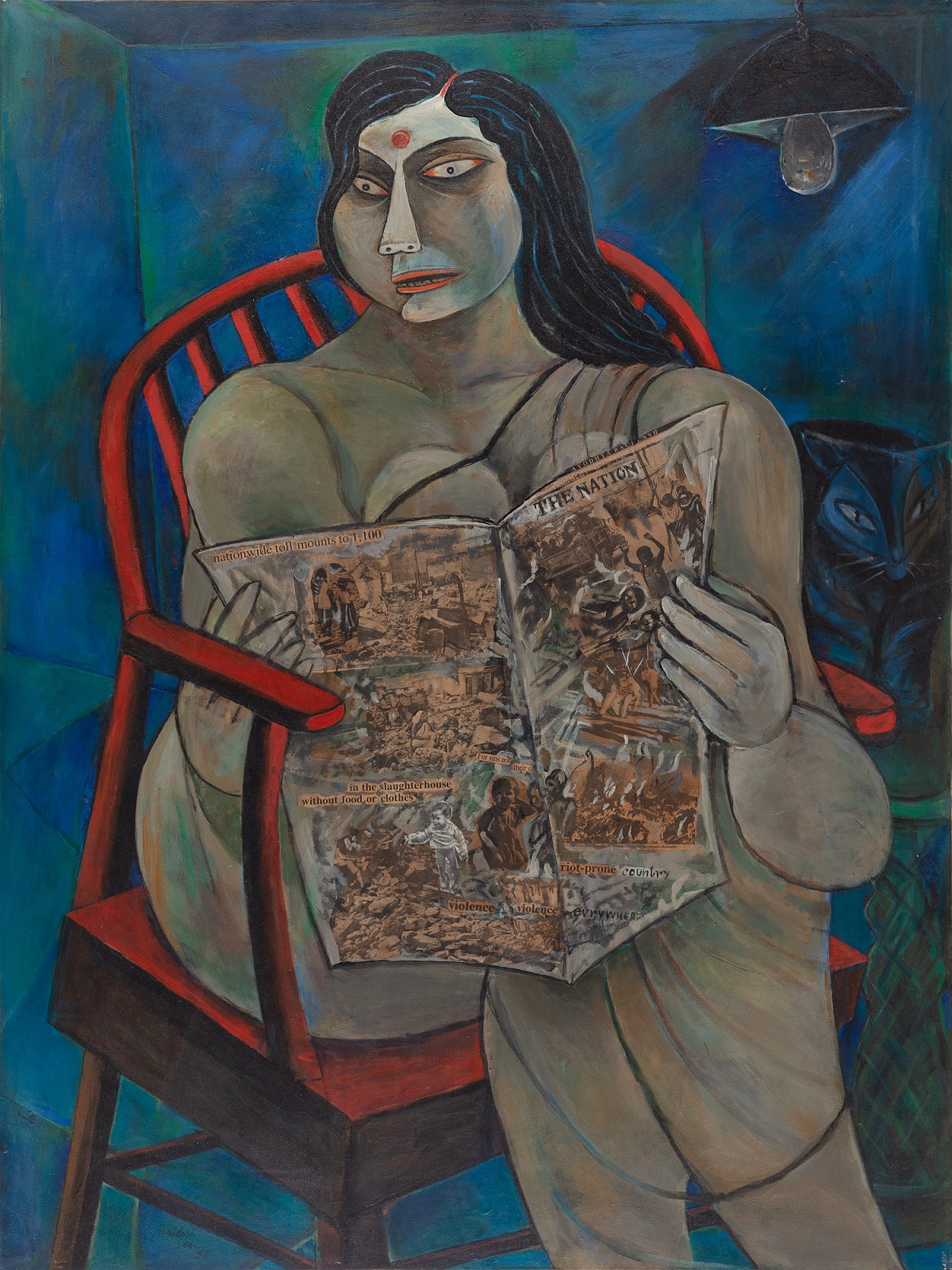

As a painter, Sen was aware of these hierarchies as he tries to differentiate between the broader varieties of humour and the more subtle manoeuvres within caricatural art that can push a work into the domain of ‘high art’. This is probably what leads him to restore the art of humour as one that is sanctioned by the ancient Indian Shilpa shastras. The art of humour or comedy, for Sen, also works as a heightened political response to the complacent norms of our time, which can breed corruption, inertia or oppression; and, as such, he contends that it falls within an artist’s purview to critique and hold up for mirth. As Ella Dutta writes, ‘From his earliest Babu series done after his return from Paris in the early 50s, an element of satire is manifest in the figuration. It is as if the artist himself is laughing and inviting his viewers to laugh at such patent signs of power and authority—the bunch of keys tied to the corner of a woman’s sari, the man smoking a hookah and seated with legs crossed on a chair. A series of watercolours on corrupt politicians debunked the netas by painting them seated on commodes with telephones in their hands. Sitting on the pot, the politician conducting his business became a figure of fun. It was not a seat of power, but a vulnerable perch that he was operating from.’ She also goes on to note the wit Sen invests in his depictions of animals and the enjoyment of everyday pleasures and laughter that can be seen in his paintings of women at leisure, speaking on the telephone, ‘lolling on cushions,…drinking green coconut water on the beach’ or taking a bath. It responds to his contention that humour in art can be spurred as much by enjoyment and happiness as anger or outrage.

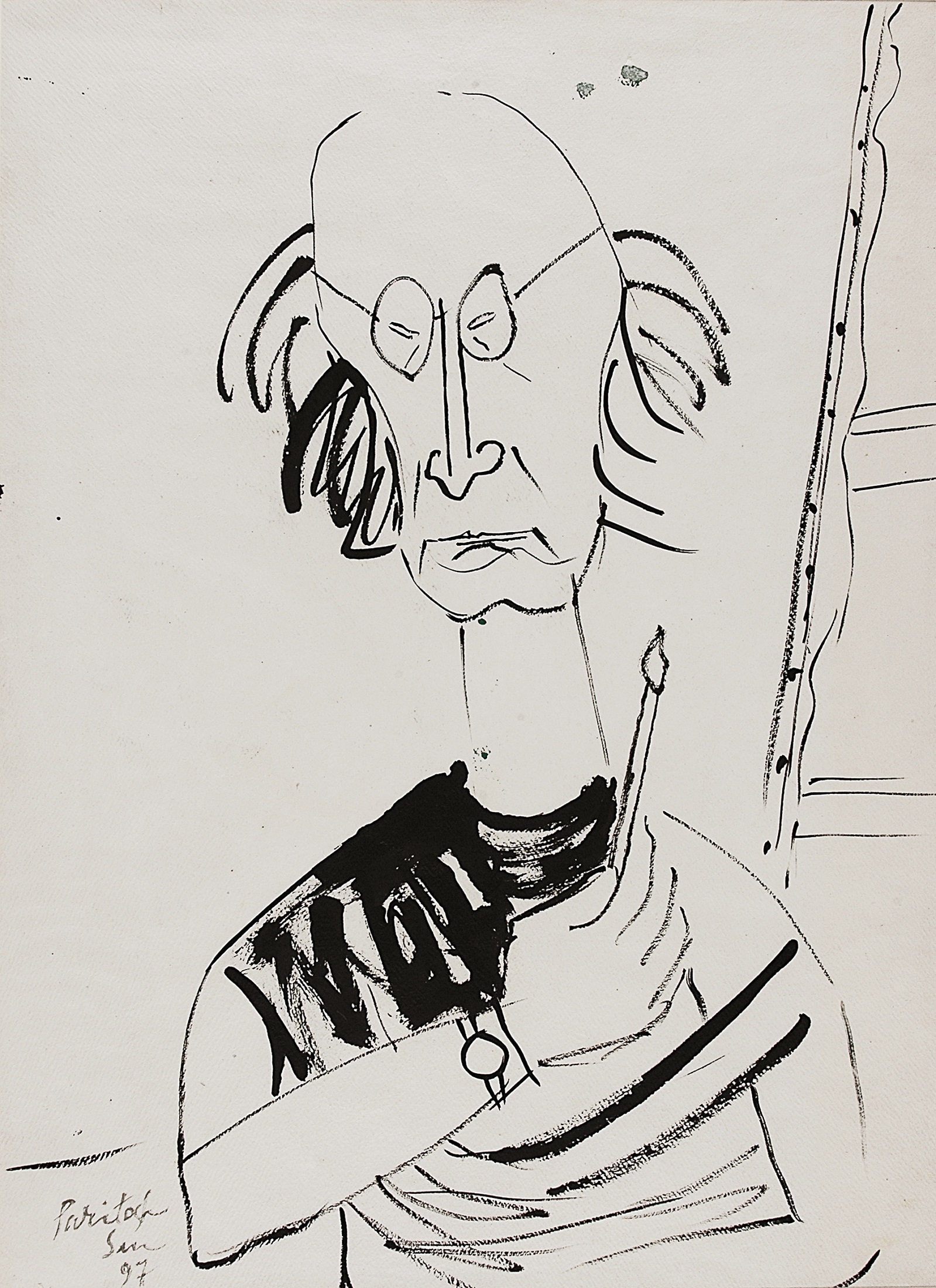

In the essay, Sen points out the lack of self-deprecation within Indian caricaturists’ work, and it is worth speculating if this is one of the reasons why he painted such a variety of self-portraits himself, each depicting the artist in frank, ludic and happy moods—giving us a break from the usual tone of sombreness that an artist adopts while depicting themselves in thought or at work.

Humour, caricature and satire in the arts

Paritosh Sen

Our Shilpa Sastras talk about the nine rasas. Erotic, comic, pathetic, furious, heroic, terrible, odious, marvelous, peaceful—all of these emotions are linked to various aspects of human sentimentality. In common parlance we often say to each other that our reality is made up of tears and laughter. It terrifies us to think of how colourless our lives would be without the presence of koutuk or the hasya rasa in it—what is termed ‘humour’ in English. The comic, that is the caricatural instinct, is a special feature of this koutuk rasa. In the classical arts or their sculpture, it can be said that the serious (or, grave) rasa dominates in temperament. This means that the typical moods associated with those arts included the heroic, the terrible, the odious and the marvelous. This holds true for both ancient as well as the classical arts.

|

Paritosh Sen, Woman Reading a Newspaper, Acrylic on canvas. Collection: DAG |

According to scholars, hasya rasa was first employed in literary fiction. Then it began to appear in the arts and, more recently, even on television. However, it can also be said that jokes, sarcasm, even irony and art originates with the presence of people or due to some special circumstances that are created by them. We have many ways to express our characters and behavioural traits, all of which provide food for laughter; and even if it seems cruel, while personal caricatural attacks or the general abundance of humour in the comic arts is widely acknowledged, it is also normal to find a predominance of themes involving painful barbs where the pitiful or the pathetic rasa takes over. In order to make a forceful impact on our mind, exaggeration is an inevitable part of both the opposite manifestations, whether it is the pleasurable rasas or the painful rasas. But this exaggeration has to be tempered. If not, one risks drawing with too broad a brush. Sarcasm, satire, humor, the more subtle it is, the more it will tickle our intellect and rank as highly valuable art (or ‘high art’). For instance, one may consider the films of Charles Chaplin. There is no need to repeat how deeply his films touch our hearts through the medium of laughter and jokes. In comparison one may say that the Laurel-Hardy movies express a broader sense of humour, giving us only temporary comic relief. This is why they leave no traces in our mind. But can one ever forget a Chaplin film after watching it once? Though ostensibly full of humor, its underlying meaning is so drenched in the pathetic rasa that it makes us think for a long time. To quote Mark Twain, ‘The secret source of humor is not joy but sorrow; there is no humor in heaven.’ I bring up Chaplin because I can’t think of a greater artist than this emperor of humour and comedy in our time. That aside, I have also written earlier about how I consider cinema to be another medium for the comic arts. It is the duty of any responsible artist to attack whatever is incongruous or wrong in human society with the sharp sword of comedy or ridicule. And this work can be done most easily, and popularly, through cartoons, than in any other medium.

|

Publicity photo from Charlie Chaplin's 1921 film, The Kid, featuring Chaplin and Jackie Coogan. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Thomas Rowlandson, Comforts of Bath: Gouty Persons Fall on Steep HIll, 1798, watercolour, 4.88 x 7.32 in. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons and Yale Center for British Art

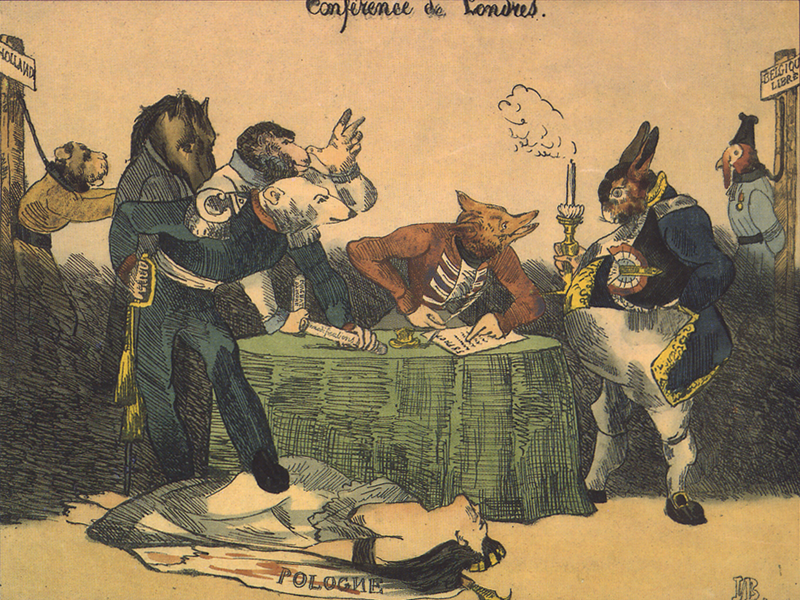

Newspapers are our indispensable daily companions. Apart from this there are weeklies, fortnightlies, monthlies, quarterlies, etc. Caricatures are usually a constant in these media, and there is no doubt today that it is a great tool to declare jihad against the reprehensible aspects of our society, such as the perpetuation of social injustice by any individual or group, which may include the practice of dowry, casteism and classism, religious superstition, oppressing women, advocating for the return of sati, and many others. Caricature as a mode of social critique was probably imported into our country from England. I write this because in the case of Europe, William Hogarth (1697-1764) was the first to satirize the idiosyncratic everyday manners of the English in his works; although the characteristic features of the English that he satirizes are applicable to people of any country. In fact, he was concerned about general human faults, weaknesses and stupidity. Another Englishman, Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827), ridiculed people by exaggerating their facial features, such as noses, eyes, faces, and limbs. These exaggerated figures or panelled cartoons first appeared in newspaper editorials in the late nineteenth century. Among the artists who became famous for drawing intense political cartoons during this period, England's Thomas Nest (sic) and France's (Honoré ) Daumier are particularly notable. Another reason to remember Daumier's name is that his contribution to European painting, as in political and social caricatures, is also quite noteworthy.

|

William Hogarth, The Painter and his Pug, 1745, 35.4 x 27.5 in. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Honoré Daumier, Conference de Londres, 1832. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

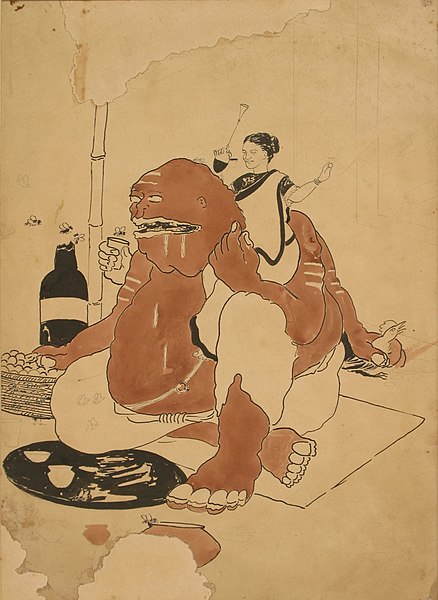

Without any comparison, I am naming an artist of our country, whose contribution is no less in this regard. The artist Gaganendranath Tagore's wonderful caricatures of various reprehensible aspects of the bourgeois society of our pre-independence era are still celebrated today. He was the first to show us that cartoons can be powerful tools for expression. In terms of style and depiction, his series of caricatural works are so strong and modern in mood that even after fifty-sixty years, their quality has not diminished. Unfortunately social caricatures are rarely seen these days...

|

Gaganendranath Tagore, Brahmin of Kaliyuga, 1917. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

I have already said that like light and shadow laughter and tears may be opposites, but they are constant companions in our lives. Even if our life can go on without tears, life without laughter, or ‘humour’, is unimaginable. We enjoy laughing and joking about other people. But how many of us—what in English is termed 'laughing at oneself'—can mock oneself? This is relevant to both our personal life and the life of the nation. Indians tend to take everything too seriously, which is why it is often difficult to spot works of light humour. But does that mean we have forgotten how to have fun? Has our sense of humour completely disappeared? I watched many plays, revues, movies and television programs while abroad. Especially in England, where kings, queens, viziers, bureaucrats, clerks, politicians have all been cast into stereotypical modes of merciless satire or caricature. Even sitting here, we have seen two such entertaining serials – 'Yes Minister' and 'Yes Prime Minister' thanks to the BBC and Doordarshan. A few years ago, I saw an American television channel taking President Reagan to task with ruthless humour. There, I also saw some films in which the various unjust aspects of the country's administration and social system have been exposed without the stitch of an excuse. And it was all done as comic entertainment. Can we think of this kind of entertainment in our country's radio, television or cinema? The sheer amount of trouble and harassment faced by the makers of the Emergency-themed movie Kissa Kursi Ka can fill up a small historical tome of its own. In a real democracy, when required, everyone, irrespective of their station in life, must stand witness in the docks of satire. This is where cartoons or caricatures become important, because this medium is neither expensive, nor time consuming. Although, theatre, cinema and television are much more powerful mediums and can strike a chord with people more easily.

Post-independence, after the pioneering age of Gaganendranath, increasing numbers of cartoonists have kept apace with the huge number of newspapers and magazines. But ninety-five percent of them are political cartoonists. Our social evils are so dire that we are not in any less need of social cartoonists. Most importantly, we need a magazine devoted to cartoons, which can caricature everything. Just like food and clothing, a nation starved of humour equally needs ‘the ability to laugh at itself’ for sustenance. Which is why we need sharp ‘wit’ because ‘wit’ and ‘humour’ are the stuff of great cartoons.

Extracted from Rong tulir baire (Beyond the paintbrush, Bhashabinyash, Kolkata, 2008)

Translated by Ankan Kazi

End Notes:

Shilpa Shastras: Translatable directly as the ‘science(s) of art and craft’, the Shilpa shastras refer to a set of ancient and medieval Hindu texts that contain instructions and manuals for making art, including sculpture, metallurgy, temple architecture and others. As scholars like Stella Kramrisch have pointed out, the ‘art’ implied by ‘shilpa’ could suggest many things such as ‘skill, craft, labor, ingenuity, rite and ritual, form and creation’. (‘Traditions of the Indian Craftsman’, 1958)

Rasa: Literally meaning ‘juice’ or essence, it denotes the suggested aesthetic flavour of a work of art, which can be determined according to the types of rasas described by Hindu philosophers like Bharata and Abhinavagupta, especially in the text Natya Shastra, attributed to the former sage. ‘The principal human feelings, according to Bharata, are delight, laughter, sorrow, anger, energy, fear, disgust, heroism, and astonishment, all of which may be recast in contemplative form as the various rasas: erotic, comic, pathetic, furious, heroic, terrible, odious, marvelous, and quietistic’. (Britannica)

Koutuk: The Bengali word koutuk suggests a ‘joke’ or a comic story, mingled with elements of mystery or curiosity. Sen goes on to use this word for the ‘new’ rasa he has in mind, koutuk rasa, similar to the hasya (laughter) rasa.

Thomas Nest (sic): Sen probably means Thomas Nast (1840—1902), the German-born American cartoonist who is considered to be the ‘Father of the American Cartoon’.

Honoré Daumier (1808—1879) was one of the major illustrators, painters and printmakers of 19th century France. He is responsible for enriching the art of political cartooning in newspapers and journals, especially through his work for the famous Parisian illustrated magazine Le Charivari.

Kissa Kursi Ka (The Tale of the Throne, 1977) is a film made by a former member of the Indian National Congress (I. N. C.) and Member of Parliament (later for the Janata Party) Amrit Nahata, and produced by Badri Prasad Joshi. Nahata made this satirical film on the politics of Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay after leaving the I. N. C. during the Emergency (1975—1977).

Wit and Humour: Sen uses the English words ‘wit’ and ‘humour’, just as he uses the English expressions ‘laughing at oneself’ and ‘the ability to laugh at itself’ earlier.