Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

Searching for the ‘Inner Form’ in Prabhakar Barwe’s Blank Canvas

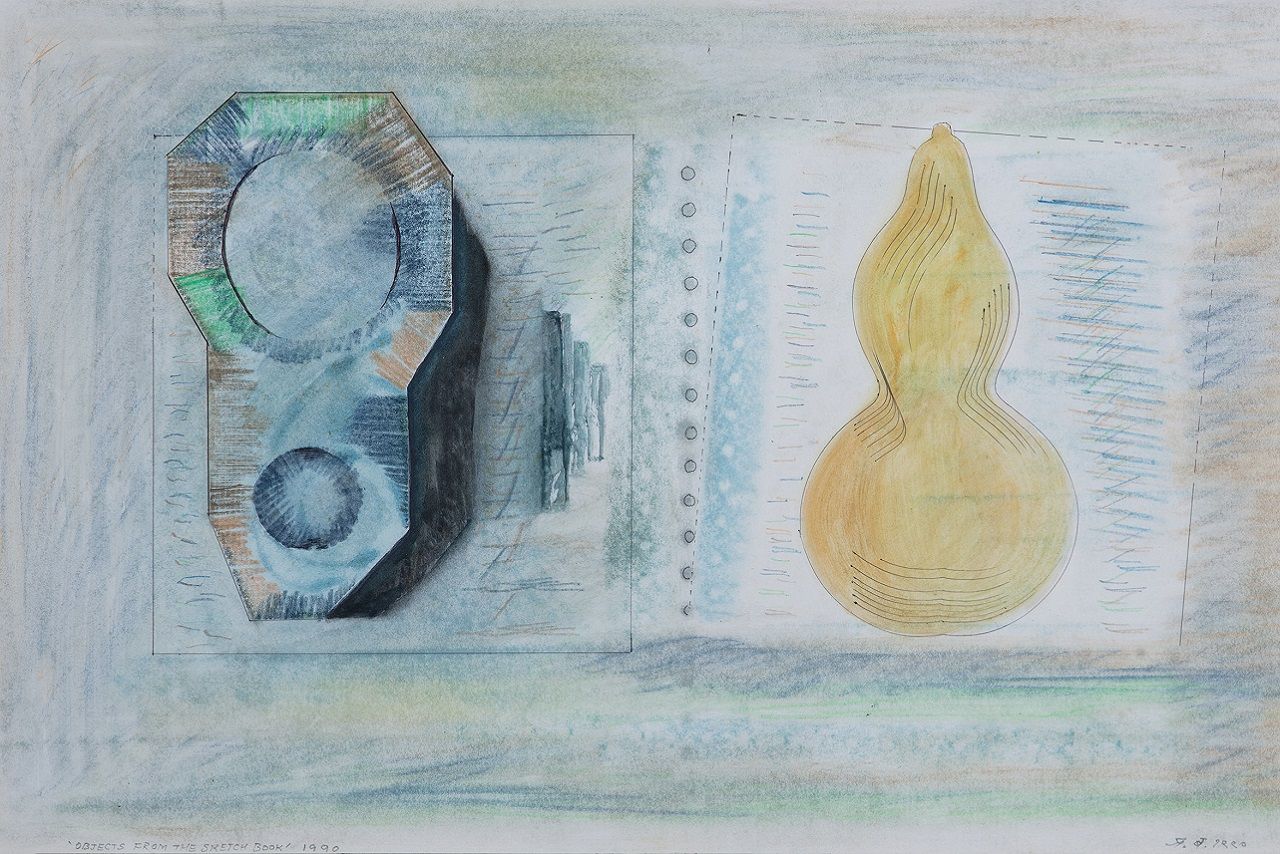

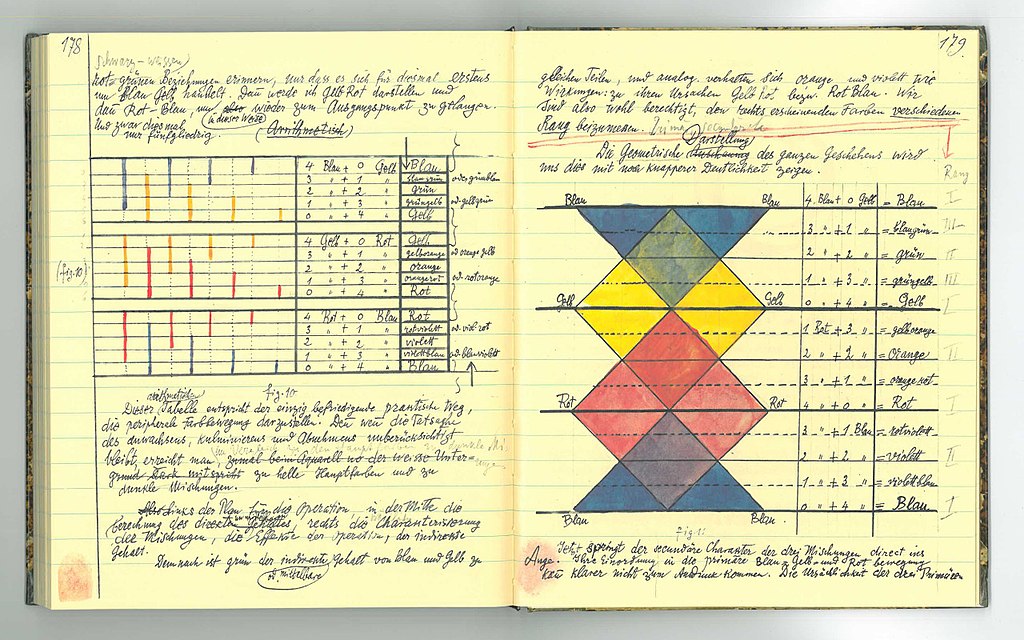

Prabhakar Barwe, Objects from the Sketch Book (detail), 1990. Collection: DAG

‘Every single object that we see- every substance, cluster of substances, why even the sky and water, have a form by which we recognize those substances and objects. This is what form means to us in everyday life. Most people don’t see the thousands of objects that are around them as forms. An artist, on the other hand, is sharply aware of the universe of forms he inhabits.

On occasion this awareness becomes so intense, that he sees not only the outward forms of objects but the smaller forms that they contain and the even subtler forms that those small forms contain. The number of increasingly subtler forms the artist may see is limited only by the power of his vision. He looks at them all as pure forms, dissociated from their functional context.’

- Prabhakar Barwe, The Blank Canvas

|

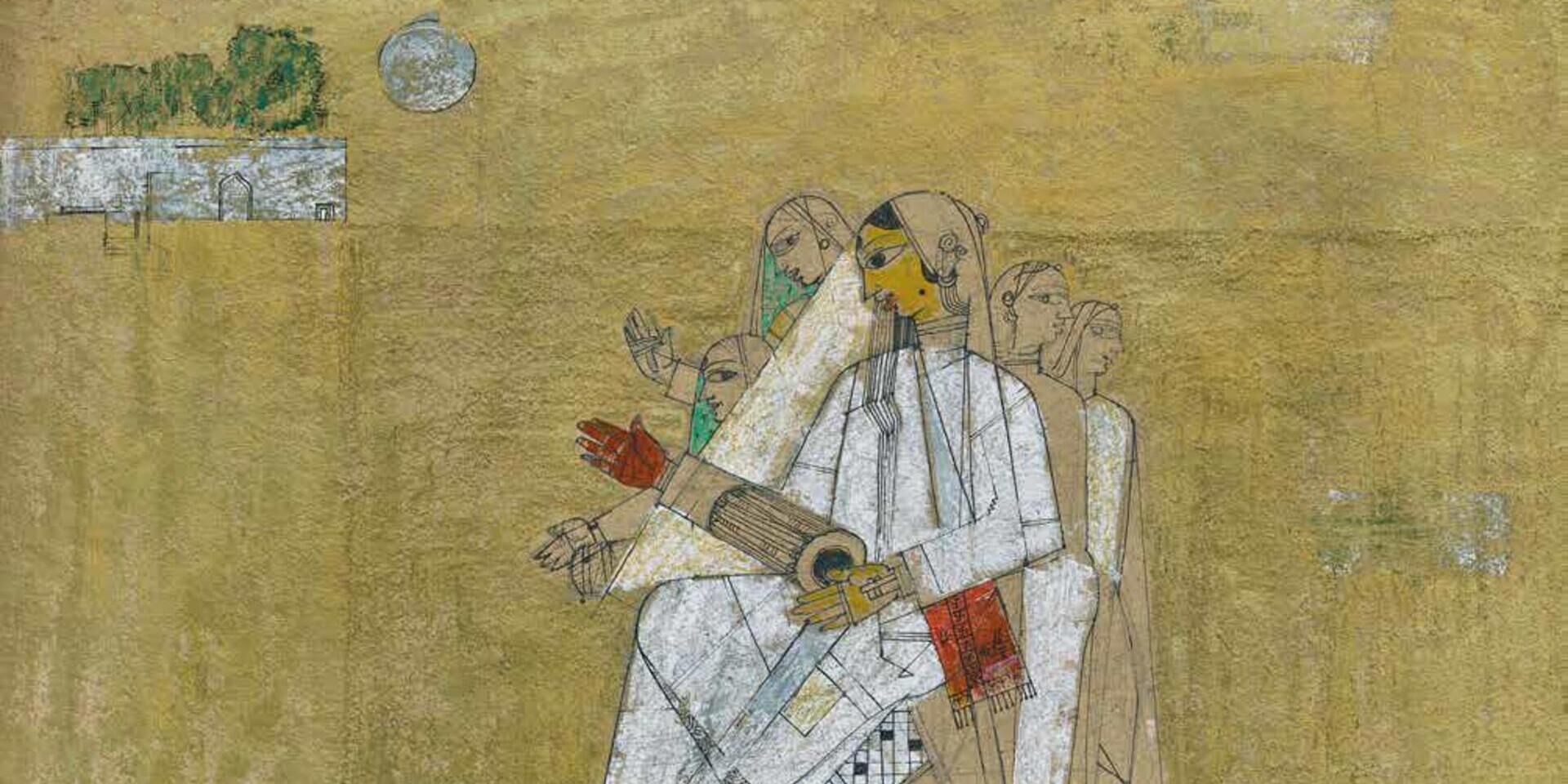

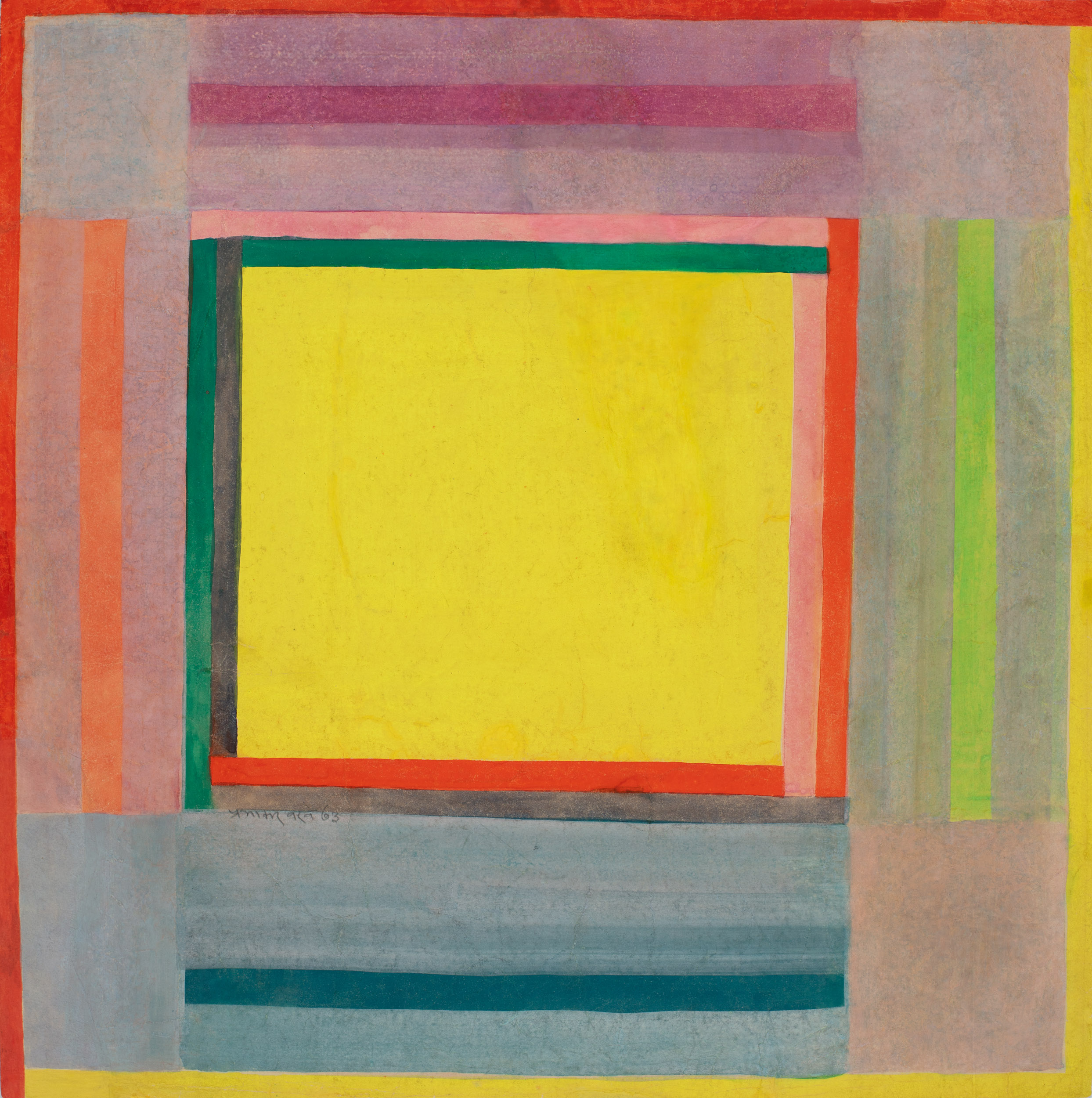

Prabhakar Barwe, Untitled, Watercolour on paper, 18.0 x 18.0 in., 1973. Collection: DAG |

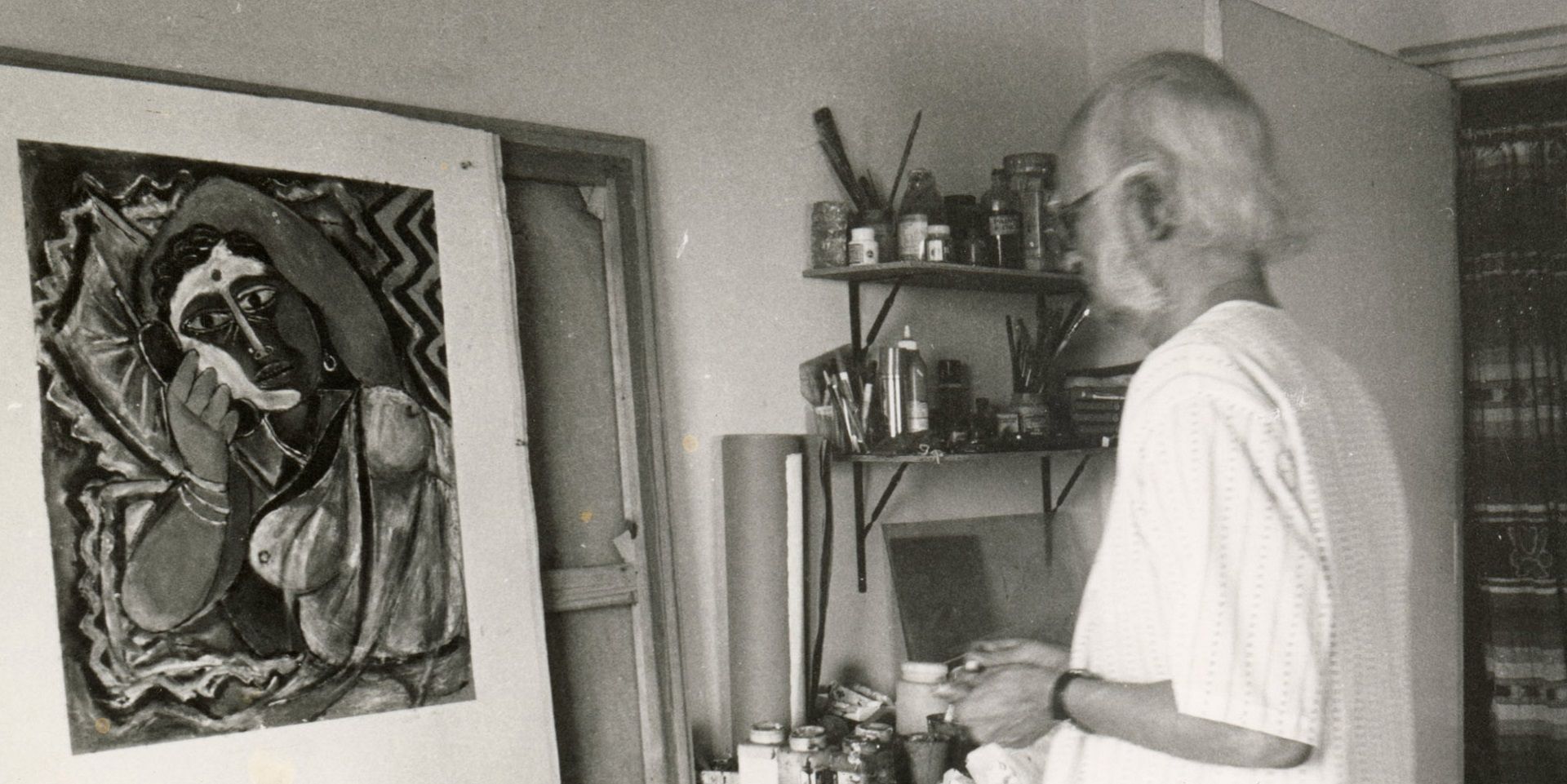

Artist and pedagogue, Prabhakar Barwe (1936—1995) intensely analysed the fundamental elements of art-making both through his art practice and his writings. Artists have often formulated their theories and observations to analyse and become aware of the cognitive modes of art making, and to associate with broader contemporaneous art movements. These manifestos become a window into an artist’s process. Prabhakar Barwe’s seminal treatise, Kora Canvas (The Blank Canvas, 1989), exemplifies his deep understanding of the fundamental elements of art and keen observations of nature and his surroundings. Barwe’s aphoristic approach to the book has been crucial in underlining the essential tropes of his practice. The book was first written by him in Marathi and was later translated into English (by Shanta Gokhale) and Hindi. His poetic descriptions give us an opportunity to take a deep dive into his mindscape.

|

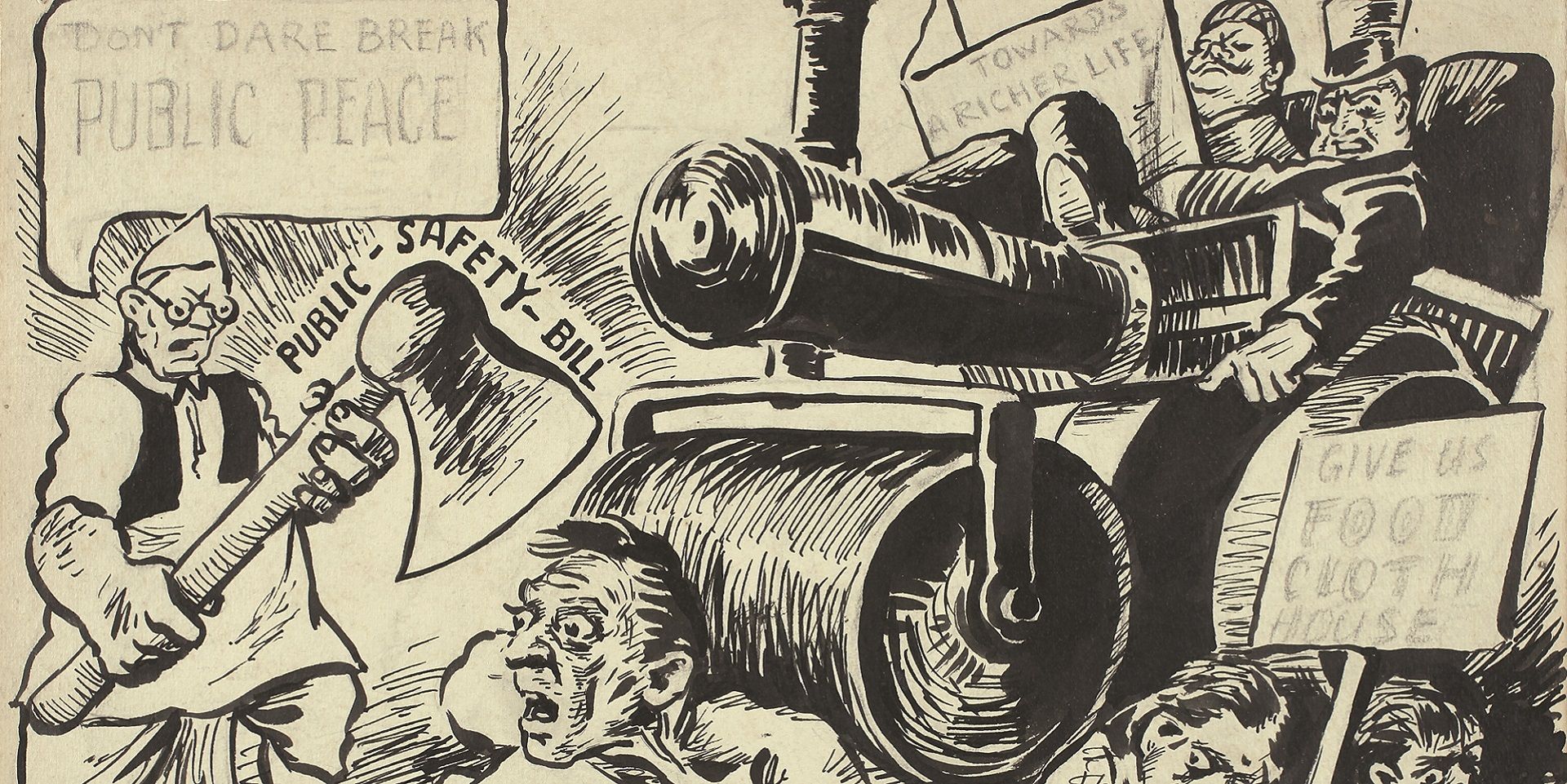

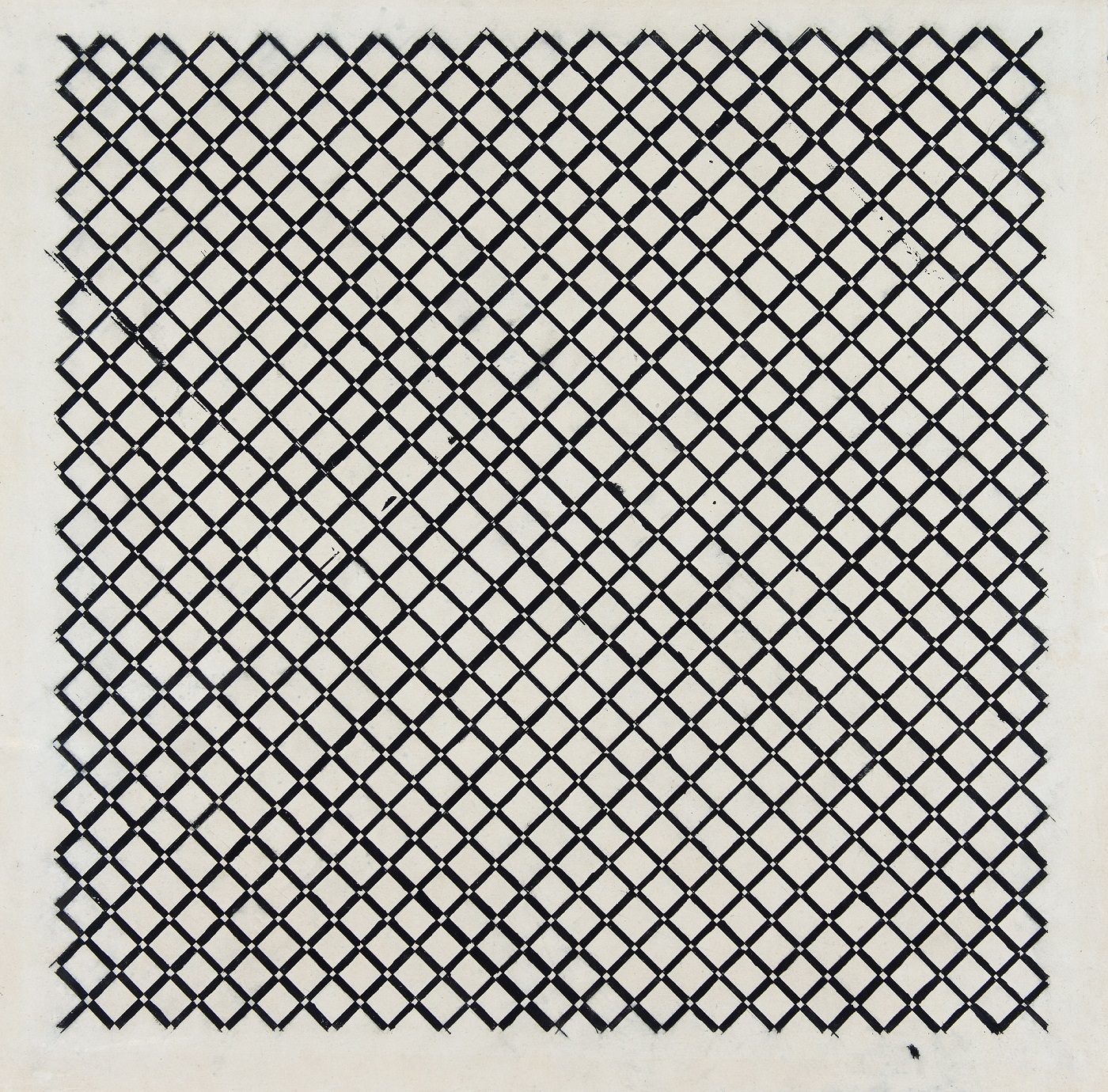

Prabhakar Barwe, Untitled, Ink on paper, 20.2 x 19.7 in. Collection: DAG |

As a modernist, he rejected the prevailing tendencies toward revivalism and developed a rather abstracted visual language, constantly gleaning from an expansive repertoire of ‘pure forms’. Figurative style was prevalent in the fifties and sixties, but it did not interest Barwe, as much as the mundane objects surrounding the human figures. He writes extensively about these hovering objects, forms or ‘symbolic signs’: ‘It is an assortment of the familiar and the unfamiliar, the concrete and the abstract. Each shape is surrounded by its own meanings and contexts. For example, a bird in a painting does not merely suggest a bird; it also expresses a certain state of the human mind. Shapes that refer in this way to something other than themselves are called symbolic shapes.’

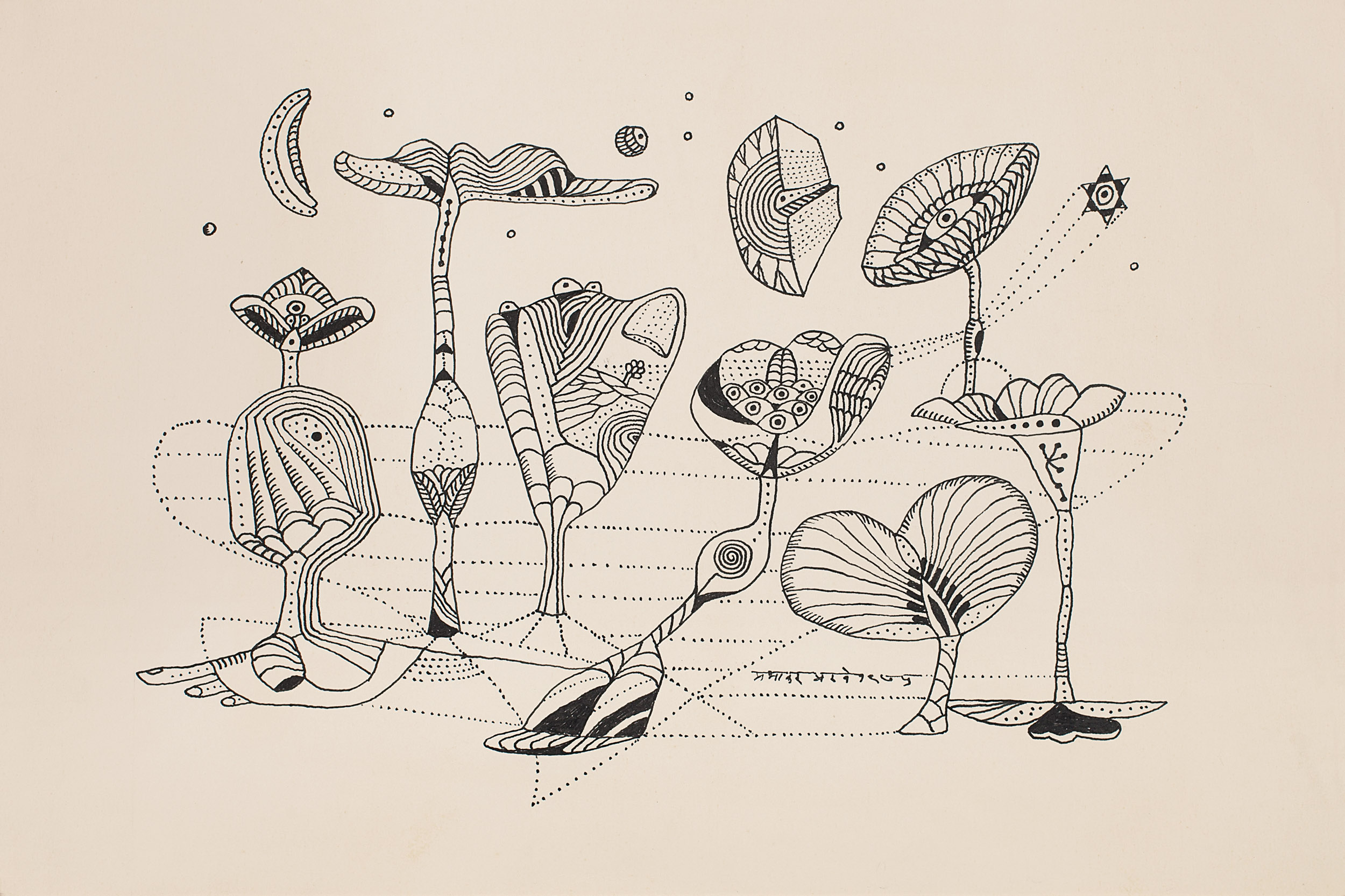

Pages from a notebook by Paul Klee, 1921-1931. Image source: Public Domain

Barwe was heavily influenced by Paul Klee (1879—1940), something that is evident in both his writings and drawings. The Swiss-born German artist was influenced by art movements like Expressionism, Cubism and Surrealism. By the early 1900s, Klee started to investigate expressive possibilities in children’s drawings and built associations with cubism, as he believed that they both returned to the very fundamentals of art. In 1920 he was appointed as a teacher for the basic design program on the mechanics of art at Bauhaus, the school of modern design at Weimar that was started in 1919. His lectures and notes expound on his excellent understanding of how formal elements of art could be used to create complex images, which were compiled in books like the Pedagogical Sketchbook and Paul Klee Notebooks. For both Klee and Barwe, their notes are clues to their art practice; they focus on the way a visual is produced, so that the formation of the artwork itself becomes paramount. In these artist books Klee and Barwe use line drawings to emphasize or even illustrate their written thoughts, where the drawings and text form an organic whole. Both have written extensively on form and attempted to expand upon it philosophically.

|

Paul Klee's Pedagogical Sketchbook, Faber & Faber, 1968. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Paul Klee writes, ‘When a linear form is combined with a plane form the linear part takes on a decidedly active character and the plane a passive character in contrast…The active part, the line, can accomplish two things by its impetus: It may divide the form into two parts, or it may go still further and give rise to a displacement.’

Barwe writes more poetically, ‘Form has many aspects…At times it grows wings and flies high into the sky, into space. Sometimes it melts like wax, while at other times it solidifies into an unmoving boulder. A form turns into flame, light, total darkness. Form flows like water, flies like a kite. Form bursts open, throwing up innumerable other forms in shards. Sometimes this very form is so fine it barely exists…..Form is independent; it is self-generated…Form is not subject to meaning. Form can move beyond meaning with perfect ease. Form owes allegiance only to space.’

Barwe’s genius lies in the way he manipulates the simple act of drawing to render complex, intriguing compositions. The manner in which Barwe carefully and meditatively draws objects, they become a mode of self-realization, reflecting his intuitive reading and aesthetic understanding, unlike the western tradition of looking at an object as a mere occasion for making still life studies. This kind of creative process could have been due to his exposure to tantra art, although it was not the spiritual aspect that drew him to tantra. He says, ‘ I am an artist and what tantra helped me was in understanding the concept of form, understanding the relationship between form and space.’

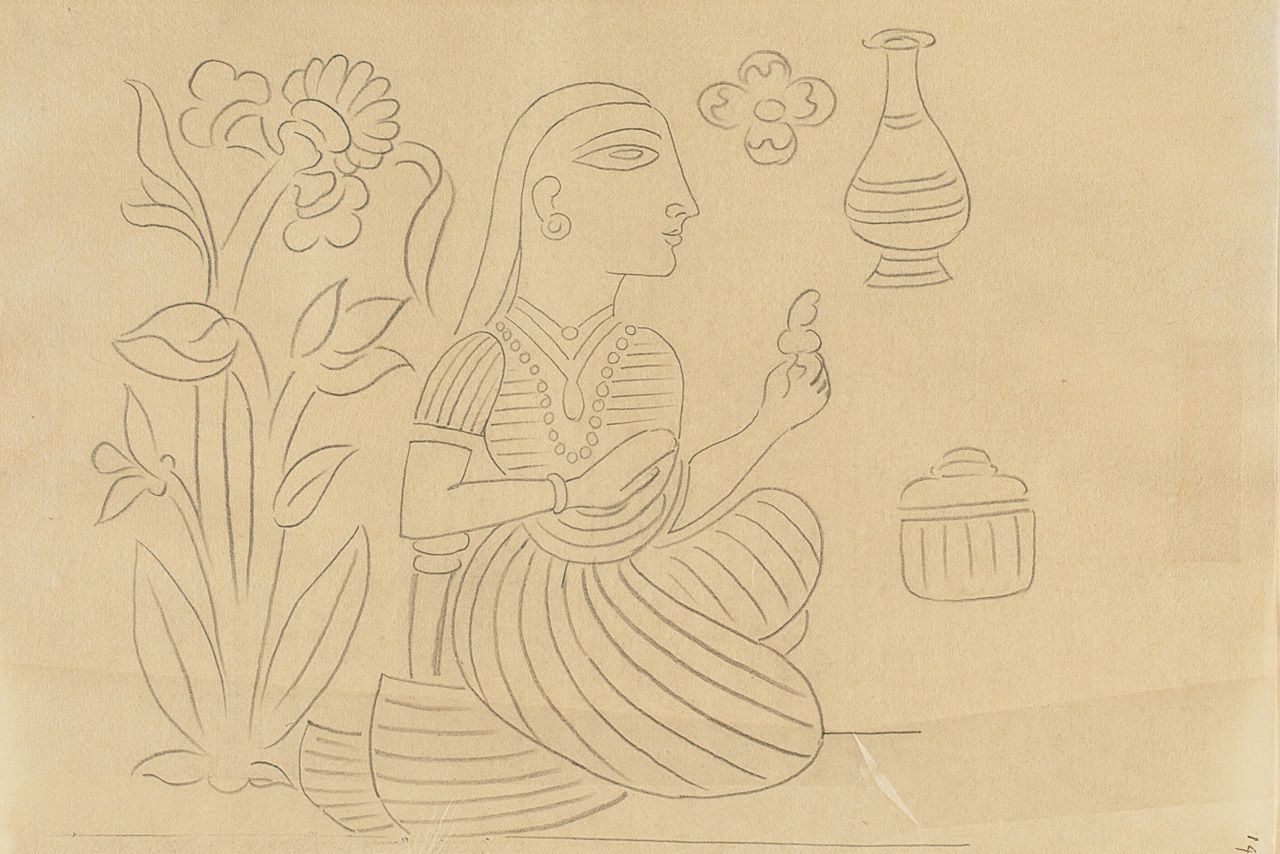

Prabhakar Barwe, Flowers of the Dawn, Ink on paper, 9.5 x 14.2 in., 1975. Collection: DAG

While Barwe writes meticulously on form and inspiration he also contributes to issues outside the scope of art making. In a fascinating instance he addresses the issue of viewership and the concern with reception. He suggests that an image is accessible or not based on whether it is familiar or unfamiliar. He establishes an artist’s true genius in rendering simple images that have a balance between the familiar and unfamiliar and suggests that when a work of art is easier to understand its meaning deepens. While he is writing broadly about abstraction, one can identify the nuances behind his style of abstraction and what he strives to achieve. Both his drawings and writings reflect his ingenious reading of an aesthetic paradigm that often lay beyond the prevalent ideas of modernism. He writes, ‘Every form carries within itself an abstract inner form or a part of itself with its own independent form. An artist might find this inner form more appealing or significant than the outer one. In his picture this form represents the essence of the whole’. In this search for the ‘inner form’ lay Barwe’s thrust towards experimentation.

Both Klee and Barwe formulated their ideas from a pedagogical point of view; and their artistic and literary practice have contributed to the movement of modernism by establishing a newfound understanding of the fundamentals of art—which they positioned at the very crux of the creative process.